From the earliest days in the history of science, there was an attempt by the reflective intellect to introduce gradations between the two poles of absolute similarity and difference in people. This was realized in a number of types, or "temperaments" - as they were then called - which classified the similarities and differences into formal categories. The Greek philosopher Empedocles tried to bring order to the chaos of natural phenomena, dividing them into four elements: earth, water, air and fire. The doctors of the time were the first to apply this principle of separation in conjunction with the doctrine of the four qualities: dry, wet, cold, warm - in relation to people, and thus they tried to reduce the confused diversity of humanity into ordered groups. The most significant in a series of such attempts were those of Galen, whose use of these teachings influenced medical science and the very treatment of patients for seventeen centuries. The very names of Galen's temperaments indicate their origin in the pathology of four "mores" or "inclinations" - qualities. Melancholic means the predominance of black bile, phlegmatic person means predominance of phlegm or mucus (the Greek word phlegm means fire, and phlegm was considered the end product of inflammation), sanguine person means predominance of blood and choleric person means predominance of yellow bile.

Today it is obvious that our modern concept of "temperament" has become much more psychological, since in the process of human development over the past two thousand years, the "soul" has been freed from any intelligible connection with cold chills and fever or from bilious or mucous secretions. Even today's doctors would not be able to compare temperament, that is, a certain type of emotional state or excitability, directly with the specificity of blood circulation or the state of lymph, although their profession and specific approach to a person from the standpoint of a physical illness tempts much more often than non-professionals, to consider mental as an end product dependent on the physiology of the glands. Humours ("juices" of the human body) of today's medicine are no longer old bodily secretions, but are more subtle hormones, sometimes to a large extent influencing "temperament" if the latter is defined as an integral sum of emotional reactions. The whole bodily make-up, its constitution in the broadest sense, have a very close relationship with psychological temperament, so we have no right to blame doctors if they consider mental phenomena to be largely dependent on the body. In a sense, the psychic is a living body, and a living body is animate matter; one way or another, there is an undisclosed unity of the psyche and the body, which needs both physical and mental study and research, in other words, this unity with necessity and equally depends on both the body and the psyche, and so much, as far as the researcher himself is inclined. Materialism of the 19th century asserted the primacy of the body, leaving the mental status of something secondary and derivative, allowing it no more reality than the so-called “epiphenomenon”. What has established itself as a good working hypothesis, namely that mental phenomena are due to physical processes, has become a philosophical presumption with the advent of materialism. Any serious science of a living organism will reject such a presumption, since, on the one hand, it constantly means that living matter is still an unsolved mystery, and on the other hand, there is enough objective evidence to recognize the presence of a completely incompatible gap between mental and physical phenomena, so that the mental area is no less mysterious than the physical one.

The materialistic presumption has become possible only recently, when a person's idea of the psychic, which has changed over the centuries, was able to free itself from old views and develop in a rather abstract direction. The ancients represented the mental and the bodily together as an inseparable unity, since they were closer to that primitive world, in which a moral crack had not yet run through the personality, and unenlightened paganism still felt inseparable, innocent and childlike, and not burdened with responsibility. The ancient Egyptians still retained the ability to indulge in naive joy when listing those sins that they did not commit: “I did not let a single person go hungry. I didn't make anyone cry. I didn't commit murder, ”and so on. Homer's heroes cried, laughed, raged, outsmarted and killed each other in a world where such things were considered natural and obvious to both humans and gods, and the Olympians had fun, spending their days in a state of unfading irresponsibility.

This happened at such an archaic level at which the pre-philosophical man existed and survived. He was completely in the grip of his own emotions. All the passions, from which his blood boiled and his heart pounded, which accelerated his breathing or forced him to hold him at all, or turned his insides inside out - all this was a manifestation of the "soul." Therefore, he placed the soul in the area of the diaphragm (phren in Greek, which also means "mind") and the heart. And only among the first philosophers the place of reason began to be attributed to the head. But even today there are tribes among blacks, whose "thoughts" are localized mainly in the abdomen, and the Pueblo Indians "think" with their hearts - only a madman thinks with his own head, they say. At this level of consciousness, the experience of sensory explosions and the feeling of self-union are essential. However, at the same time silent and tragic for an archaic person who began to think was the appearance of the dichotomy that Nietzsche put at the door of Zarathustra: the discovery of pairs of opposites, the division into even and odd, upper and lower, good and evil. This was the work of the ancient Pythagoreans, which became their doctrine of moral responsibility and the serious metaphysical consequences of sin, a doctrine that gradually over the centuries seeped into all social strata, mainly due to the spread of the Orphic and Pythagorean mysteries. Even Plato used the parable of the white and black horses to illustrate the stubbornness and polarity of the human psyche, and even earlier the Mysteries proclaimed the doctrine of good, rewarded in the future, and evil, punished in hell. These teachings could not be rejected as mystical nonsense and deception of philosophers from the "wilderness", as stated by Nietzsche, or as sectarian hypocrisy, since already in the VI century BC. NS. Pythagoreanism was something of a state religion throughout the territory of Graecia Magna (Magna Graecia). In addition, the ideas that formed the basis of these mysteries never died, but experienced a philosophical renaissance in the 2nd century BC. e., when they had a huge impact on the world of Alexandrian thought. Their clash with the prophecy of the Old Testament subsequently led to what can be called the beginning of Christianity as a world religion.

Now, from the Hellenistic syncretism, the division of people into types arises, which was completely not characteristic of the "humoral" psychology of Greek medicine. In a philosophical sense, here gradations arose between the Parmenidean poles of light and darkness, top and bottom. People began to be divided into hylikoi, psychics (psychikoi) and pneumaticoi, highlighting, respectively, material, mental and spiritual being. Such a classification is, of course, not a scientific formulation of similarities and differences - it is a critical value system based not on the behavior and appearance of a person as a phenotype, but on definitions of ethical, mystical and philosophical properties. Although the latter are not exactly "Christian" concepts, they nevertheless form an integral part of early Christianity in the time of St. Paul. Its very existence is irrefutable proof of the split that arose in the original unity of a person who was completely at the mercy of his emotions. Before this, a person appeared to be an ordinary living being and remained in this capacity only a toy of experience, of his experiences, incapable of any reflective analysis regarding his origin and his fate. And now, suddenly, he found himself facing three fateful factors - endowed with body, soul and spirit, to each of which he had a moral obligation. Presumably already at birth, it was decided whether he would spend his life in a hylic or pneumatic state, or in some indeterminate location between them. The deeply ingrained dichotomy of the Greek mind made the latter sharper and more insightful, and the resulting emphasis now shifted significantly to the psychic and spiritual, leading to the inevitable separation from the Hylic region of the body. All the highest and ultimate goals lay in the moral destiny of man, in his spiritual supermundane and supermundane final sojourn, and the separation of the Hilic region turned into a stratification between the world and the spirit. Thus, the original courteous wisdom expressed in the Pythagorean pairs of opposites became a passionate moral conflict. Nothing, however, is capable of stirring up our self-awareness and alertness as much as a state of war with ourselves. One can hardly think of any other more effective means to awaken human nature from an irresponsible and innocent half-asleep primitive mentality and bring it to a state of conscious responsibility.

This process is called cultural development. In any case, it is the development of the human ability to discriminate and the ability to judge - consciousness in general. With an increase in knowledge and an increase in critical ability, the foundations were laid for the widespread subsequent development of the human mind in terms of (in terms of) intellectual achievement. Science became a special mental product that far surpassed all the achievements of the ancient world. It closed the rift between man and nature in the sense that, although man was separated from nature, science gave him the opportunity to find again his corresponding place in the natural order of things. However, his special metaphysical position had to be thrown overboard, rejected to the extent that it was not provided by faith in traditional religion - hence the well-known conflict between "faith and knowledge." If anything, science has accomplished an excellent rehabilitation of matter, and in this respect materialism can even be seen as an act of historical justice.

But one, undoubtedly very important, area of experience, the human psyche itself, for a very long time remained a reserved area of metaphysics, although after the Enlightenment, more and more serious attempts were made to make it accessible to scientific research. The first experimental experiments were made in the field of sensory perception, and then gradually moved into the field of associations. This line of research paved the way for experimental psychology, culminating in Wundt's "physiological psychology". A more descriptive approach to psychology, with which the medical profession soon came into contact, developed in France. Its main representatives were Teng, Ribot and Janet. This direction mainly characterized the fact that in it the psychic was subdivided into separate mechanisms or processes. In light of these attempts, today there is an approach that could be called "holistic" - the systematic observation of the mental as a whole. Much indicates that this trend originated in a certain biographical type, in particular in the type that, in the ancient era, also having its own specific advantages, was described as "an amazing fate." In this connection, I think of Justin Kerner and his Seeress of Prevorst and the case of Bloomhardt the Elder and his medium Gottliebin Dittus. However, to be historically fair, I must remember to mention the medieval Acta Sanctorum.

This line of research continued in later works associated with the names of William James, Freud, and Theodore Flournoy. James and his friend Flurnoy, a Swiss psychologist, made an attempt to describe the holistic phenomenology of the psyche, and also to view it as something whole. Freud, as a doctor, took the integrity and inseparability of the human personality as a starting point, although, in accordance with the spirit of the times, he limited himself to the study of instinctive mechanisms and individual processes. He also narrowed the picture of man to the integrity of a very important "bourgeois" collective personality, and this inevitably led him to philosophically one-sided interpretations. Freud, unfortunately, could not resist the temptations of a physician and reduced everything mental to the physical, doing it in the manner of the old "humoral" psychologists, not without revolutionary gestures towards those metaphysical reserves for which he harbored sacred fear.

Unlike Freud, who, after a correct psychological start, turned back towards the ancient assumption of the supremacy (sovereignty, independence) of the physical constitution and tried to return back to a theory in which instinctive processes are conditioned by bodily processes, I start with the premise of the supremacy of the mental. Since the physical and mental in a sense form a unity - although they are completely different in the manifestations of their nature - we cannot but attribute reality to each of them. Until we have a way to comprehend this unity, there is nothing left but to study them separately and temporarily treat them as independent of each other, at least in their structure. But the fact that they are not like that can be observed every day on ourselves. Although if we limited ourselves only to this, we would never be able to understand anything in the psychic in general.

Now, if we assume the independent supremacy of the psychic, then we will free ourselves from - for the moment - the insoluble task of reducing the manifestations of the psychic to something definitely physical. We can then accept manifestations of the psychic as expressions of its inner being and try to establish certain similarities and correspondences or types. Therefore, when I talk about psychological typology, I mean by this the formulation of the structural elements of the mental, and not the description of mental manifestations (emanations) of the individual type of constitution. The latter, in particular, is considered in studies on the structure of the body and character of Kretschmer.

In my book "Psychological Types" I gave detailed description exclusively psychological typology. The research I did was based on twenty years of medical practice, which allowed me to get in close contact with people of all classes and levels from around the world. When you start as a young doctor, your head is still full of clinical cases and diagnoses. Over time, however, impressions of a completely different kind accumulate. Among them - a staggering huge variety of human individuals, a chaotic abundance of individual cases. The specific circumstances around them, and above all the specific characters themselves, create clinical pictures, pictures that, even with all the desire, can be squeezed into the straitjacket of a diagnosis only by force. The fact that a particular disorder may be given a particular name seems completely inappropriate next to the overwhelming impression that all clinical pictures are numerous imitative or stage demonstrations of certain specific character traits. The pathological problem to which it all boils down, in fact, has nothing to do with clinical picture, but, in fact, is an expression of character. Even the complexes themselves, these "nuclear elements" of neurosis, are, among other things, simple attendant circumstances of a certain characterological predisposition. This is most easily seen in relation to the patient's parental family. Let's say he is one of four children of his parents, neither the youngest nor the oldest, has the same education and conditioned behavior as the others. However, he is sick and they are healthy. Anamnesis shows that the entire series of influences to which he, like others, was exposed and from which they all suffered, had a pathological effect only on him - at least outwardly, apparently. In fact, these influences, and in his case, were not etiological factors, and it is not difficult to be convinced of their falsity. The real cause of a neurosis lies in the specific way in which it reacts and assimilates these environmental influences.

Comparing many such cases, it gradually became clear to me that there must be two fundamentally different general attitudes that divide people into two groups, providing all of humanity with the possibility of a highly differentiated individual. Since it is obvious that this is not the case itself as such, we can only say that this difference in attitudes turns out to be easily observable only when we are faced with a relatively well-differentiated personality, in other words, it acquires practical importance only after reaching a certain degree of differentiation. Pathological cases of this kind are almost always people who deviate from the familial type and as a result find no longer sufficient protection in their inherited instinctual basis. Weak instincts are one of the primary reasons for the development of the habitual one-sided attitude, although, in extreme cases, this is due to or supported by heredity.

I have called these two fundamentally different attitudes extraversion and introversion. Extraversion is characterized by interest in an external object, responsiveness and readiness to perceive external events, the desire to influence and be influenced by events, the need to interact with the outside world, the ability to endure confusion and noise of any kind, and in fact find pleasure in it, the ability to hold constant attention to the world around you, to make many friends and acquaintances without much, however, analysis and ultimately the presence of a feeling of great importance to be close to someone chosen, and therefore a strong tendency to demonstrate oneself. Accordingly, the life philosophy of the extrovert and his ethics carry, as a rule, a highly collectivist nature (beginning) with a strong inclination towards altruism. His conscience is heavily influenced by public opinion. Moral apprehension occurs mainly when “other people know”. The religious convictions of such a person are determined, so to speak, by a majority vote.

The real subject, the extrovert as a subjective being, is - as far as possible - immersed in darkness. He hides his subjective origin from himself under the cover of the unconscious. The reluctance to subordinate one's own motives and impulses to critical thinking is expressed very clearly. He has no secrets, he cannot keep them for a long time, because he shares everything with others. If something that cannot be mentioned touches him, such a person will prefer to forget it. Anything that might tarnish the parade of optimism and positivism is avoided. Whatever he thinks about, whatever he does or intends to do, it is conveyed convincingly and warmly.

The mental life of a given personality type is played out, so to speak, outside of himself, in the environment. He lives in others and through others - any thoughts about himself make him shudder. The dangers hiding there are best overcome by noise. If he has a "complex", he finds refuge in social circles, turmoil and allows several times a day to be assured that everything is in order. In the event that he does not interfere too much in other people's affairs, is not too assertive and not too superficial, he can be a pronounced useful member of any community.

In this short article I have to be content with a cursory sketch. I just intend to give the reader some idea of what extraversion is, something that he can align with his own knowledge of human nature. I deliberately began with a description of extraversion, since this attitude is familiar to everyone - the extravert not only lives in this attitude, but also demonstrates it in front of his comrades in every possible way out of principle. In addition, such an attitude is consistent with certain generally recognized ideals and moral principles.

Introversion, on the other hand, directed not at the object but at the subject and not oriented by the object, is not so easily observable. The introvert is not so accessible, he seems to be in a constant retreat in front of the object, gives in to him. He keeps away from external events, without entering into interrelation with them, and shows a distinct negative attitude towards society as soon as he finds himself among a fair number of people. In large companies, he feels lonely and lost. The thicker the crowd, the stronger its resistance grows. At least he is not "with her" and has no love for gatherings of enthusiasts. He cannot be classified as a sociable person. What he does, he does in his own way, shielding himself from outside influences. Such a person tends to look awkward, awkward, often deliberately restrained, and it just so happens that either because of a certain impudence of manner, or because of his gloomy inaccessibility, or something done inappropriately, he unwittingly hurts people. Their best qualities he reserves it for himself and generally does his best to keep silent about them. He easily becomes distrustful, self-willed, often suffers from inferiority of his feelings and for this reason is also envious. His ability to comprehend the object is carried out not because of fear, but because the object seems to him negative, demanding attention, insurmountable or even threatening. Therefore, he suspects everyone of "all mortal sins", all the time he is afraid of being a fool, so he usually turns out to be very touchy and irritable. He surrounds himself with the barbed wire of difficulties so tightly and impenetrably that in the end he himself prefers to do something than sit inside. He confronts the world with a carefully designed defensive system, made up of scrupulousness, pedantry, moderation and thrift, prudence, "high-lipped" correctness and honesty, painful conscientiousness, politeness and open distrust. In his picture of the world there are few pink colors, since he is supercritical and will find hair in any soup. Under normal circumstances, he is pessimistic and worried, because the world and human beings are not kind one iota and seek to crush him, so that he never feels accepted and favored by them. But he himself also does not accept this world, at least not completely, not completely, since at first everything must be comprehended and discussed by him according to his own critical standards. Ultimately, only those things are accepted from which, for various subjective reasons, he can derive his own benefit.

For him, any thoughts and thoughts about himself are sheer pleasure. His own world is a safe haven, a carefully tended and walled garden, closed to the public and hidden from prying eyes. The best is your own company. He feels at home in his world, and only he himself makes any changes in it. His best job is done with the involvement of their own capabilities, on their own initiative and in their own way. If he succeeds after a long and exhausting struggle to master something alien to him, then he is able to achieve excellent results. The crowd, the majority of views and opinions, public rumor, general enthusiasm will never convince him of anything, but, rather, will force him to hide even deeper in their shell.

His relationships with other people grow warmer only in conditions of guaranteed security, when he can put aside his defensive distrust. Since this happens to him infrequently, the number of his friends and acquaintances is therefore very limited. So the psychic life of this type is played out entirely within. And if difficulties and conflicts arise there, then all doors and windows are tightly closed. The introvert closes in on himself, along with his complexes, until he ends up in complete isolation.

Despite all these characteristics, the introvert is by no means a social loss. His withdrawal into himself does not represent a final self-denial of the world, but a search for reassurance in which solitude enables him to contribute to the life of the community. This type of personality is the victim of numerous misunderstandings - not because of injustice, but because he himself causes them. He also cannot be free from accusations of secret pleasure from the hoax, because such a misunderstanding brings him a certain satisfaction, since it confirms his pessimistic point of view. From all this it is not difficult to understand why he is accused of coldness, pride, stubbornness, selfishness, self-righteousness and vanity, capriciousness and why he is constantly admonished that loyalty to the public interest, sociability, imperturbable sophistication and selfless trust in powerful authority are true virtues and testify to healthy and an energetic life.

The introvert quite understands and recognizes the existence of the above virtues and admits that somewhere, perhaps - just not in the circle of his acquaintances - and there are wonderful spiritualized people who enjoy the undiluted possession of these ideal qualities. But self-criticism and awareness of his own motives rather quickly lead him out of the delusion about his ability to such virtues, and an incredulous sharp look, aggravated by anxiety, allows him to constantly find donkey ears sticking out from under a lion's mane in his companions and fellow citizens. Both the world and people are for him troublemakers and a source of danger, not delivering him an appropriate standard by which he could ultimately navigate. The only thing that is indisputably true for him is his subjective world, which - as sometimes, in moments of social hallucinations, appears to him - is objective. It would be very easy to accuse such people of the worst kind of subjectivism and of unhealthy individualism, if we were without any doubts about the existence of only one objective world. But such a truth, even if it exists, is not an axiom - it is only half of the truth, the other half of it is that the world also exists in the form in which it is seen by people and, ultimately, by the individual. No world simply does not exist and does not exist without a discerning subject who learns about it. The latter, no matter how small and imperceptible it may seem, is always another pillar that supports the entire bridge of the phenomenal world. The attraction to the subject therefore has the same validity as the attraction to the so-called objective world, since this world is based on psychic reality itself. But at the same time it is also a reality with its own specific laws, which by their nature do not belong to derivatives, secondary.

Two attitudes, extraversion and introversion, are opposite forms, which made themselves known to no less extent in the history of human thought. The problems they raised were largely foreseen by Friedrich Schiller and lie at the heart of his Letters on Aesthetic Education. But since the concept of the unconscious was not yet known to him, Schiller could not achieve a satisfactory solution. But, in addition, the philosophers, who were much better equipped in terms of deeper advancement in this issue, did not want to subordinate their thinking function to thorough psychological criticism and therefore remained aloof from such discussions. It should be clear, however, that the inner polarity of such an attitude has a very strong influence on the philosopher's own point of view.

For an extrovert, an object is interesting and attractive a priori, just as the subject or psychic reality is for an introvert. Therefore, we could use the expression "numinal accent" for this fact, by which I mean that for an extrovert the quality of positive meaning, importance and value is assigned primarily to the object, so that the object plays a dominant, defining and decisive role in all mental processes from the very beginning, just as the subject does for the introvert.

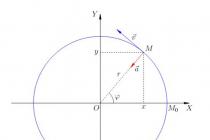

But the numinal accent does not decide the matter only between the subject and the object - it also chooses the conscious function, which is mainly used by this or that individual. I distinguish four functions: thinking, feeling, sensing, and intuition. The functional essence of sensation is to establish that something exists, thinking tells us what this something means, feeling - what is its value, and intuition suggests where it came from and where it should go. I call sensation and intuition irrational functions because they both deal directly with what is happening and with actual or potential realities. Thinking and feeling, being distinctive functions, are rational. Sensation, the function of "reality" (fonction du reel), excludes any simultaneous intuitive activity, since the latter is not at all concerned with the present, but is rather a sixth sense for hidden opportunities and therefore must not allow herself to be influenced by existing reality. In the same way, thinking is the opposite of feeling, since thinking should not be influenced or deviated from its goals depending on sensory assessments, just as feeling usually deteriorates in the captivity of too strong reflection. These four functions, arranged geometrically, form a cross with the axis of rationality running at right angles to the axis of irrationality.

The four orienting functions, of course, do not contain everything that is contained in the conscious psyche. Will and memory, for example, are not included. The reason is that the differentiation of these four orienting functions is, in fact, an empirical sequence of typical differences in the functional attitude. There are people in whom the numinal emphasis falls on sensation, on the perception of facts, and elevates it to the only defining and all-pervasive principle. These people are focused on reality, on fact, on an event, and their intellectual judgment, feeling and intuition recede into the background under the overarching importance of real facts. When the emphasis falls on thinking, then judgment is based on what meaning should be attributed to the facts in question. And the way in which the individual deals with the facts themselves will depend on this meaning. If feeling turns out to be numinal, then the adaptation of the individual will entirely depend on the sensory assessment that he ascribes to these facts. Finally, if the numinal emphasis is on intuition, then actual reality is only considered to the extent that it appears to harbor opportunities becoming the main driving force, regardless of the way in which real things are presented in the present.

Thus, the localization of the numinal accent gives rise to four functional types, which I first encountered in my relationships with people, but systematically formulated only much later. In practice, these four types are always combined with the type of attitude, that is, with extraversion or introversion, so that the functions themselves appear in an extraverted or introverted version. This creates a structure of eight descriptive functional types. Obviously, within the framework of the essay, it is impossible to present the very psychological specifics of these types and to trace their conscious and unconscious manifestations. Therefore, I must refer interested readers to the above study.

The purpose of psychological typology is not to classify people into categories — that in itself would be a rather pointless affair. Rather, its purpose is to provide critical psychology with the opportunity to carry out methodological research and the presentation of empirical material. First, it is a critical tool for the researcher in need of reference points of view and a guideline if he seeks to reduce the chaotic excess of individual experience to some order. In this respect, typology can be compared to a trigonometric grid or, better still, to a crystallographic system of axes. Secondly, typology is a great help in understanding the wide variety that occurs among individuals, and it also provides a key to fundamental differences in existing psychological theories. Last but not least, it is an essential tool for defining the "personality equation" practical psychologist, who, armed with accurate knowledge of his differentiated and subordinate functions, can avoid many serious errors in patient care.

The typological system I propose is an attempt, based on practical experience, to provide an explanatory basis and a theoretical framework for the limitless variety that previously prevailed in the formation of psychological concepts. In such a young science as psychology, the limitation of concepts will sooner or later become an inevitable necessity. Someday psychologists will be forced to agree on a set of basic principles to avoid controversial interpretations, if psychology is not going to remain an unscientific and random conglomeration of individual opinions.

Jung Carl Gustav

Psychological types

Carl Gustav Jung

Psychological types

Carl Gustav Jung and Analytical Psychology. V.V. Zelensky

Foreword. V.V. Zelensky

From the editor of the Russian edition of 1929 E. Medtner

Preface to the first Swiss edition

Preface to the seventh Swiss edition

Preface to the Argentine edition

Introduction

I. The problem of types in the history of ancient and medieval thought

1. Psychology of the classical period: Gnostics, Tertullian, Origen

2. Theological controversy in the early Christian Church

3. The problem of transubstantiation

4. Nominalism and realism

5. The controversy between Luther and Zwingli about the sacrament

II. Schiller's Ideas on the Type Problem

1. Letters about aesthetic education of a person

2. Reasoning about naive and sentimental poetry

III. Apollonian and Dionysian beginning

IV. The problem of types in human studies

1. General overview of Jordan's types

2. Special exposition and criticism of Jordan's types

V. The problem of types in poetry. Prometheus and Epimetheus by Karl Spitteler

1. Preliminary notes on typing Spitteler

2. Comparison of Prometheus Spitteler with Prometheus Goethe

3. The meaning of the unifying symbol

4. Symbol relativity

5. The nature of Spitteler's unifying symbol

Vi. The problem of types in psychopathology

Vii. The problem of typical attitudes in aesthetics

VIII. The problem of types in modern philosophy

1. Types according to James

2. Characteristic pairs of opposites in James types

3. To criticism of James's concept

IX. The problem of types in biography

X. General description of types

1. Introduction

2. Extraverted type

3. Introverted type

XI. Definition of terms

Conclusion

Applications. Four works on psychological typology

1. To the question of learning psychological types

2. Psychological types

3. Psychological theory of types

4. Psychological typology

Carl Gustav Jung and Analytical Psychology

Among the most prominent thinkers of the 20th century, we can confidently name the Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung.

As you know, analytical, or more precisely, depth psychology is a general designation of a number of psychological trends that put forward, among other things, the idea of the independence of the psyche from consciousness and strive to substantiate the actual existence of this psyche independent of consciousness and reveal its content. One of such directions, based on the concepts and discoveries in the field of the mental, made by Jung at different times, is analytical psychology. Today in the everyday cultural environment such concepts as complex, extrovert, introvert, archetype, once introduced into psychology by Jung, have become common and even stereotyped. There is a misconception that Jung's ideas grew out of idiosyncratic psychoanalysis. And although a number of Jung's propositions are indeed based on objections to Freud, the very context in which "building elements" arose in different periods, which later formed the original psychological system, of course, is much broader and, most importantly, it is based on ideas and views different from Freud's. both on human nature and on the interpretation of clinical and psychological data.

Carl Jung was born on July 26, 1875 in Kesswil, canton of Thurgau, on the shores of the picturesque Lake Constance, in the family of a pastor of the Swiss Reformed Church; my father's grandfather and great-grandfather were doctors. He studied at the Basel gymnasium, favorite subjects of the gymnasium years were zoology, biology, archeology and history. In April 1895 he entered the University of Basel, where he studied medicine, but then decided to specialize in psychiatry and psychology. In addition to these disciplines, he was deeply interested in philosophy, theology, occultism.

After graduating from medical school, Jung wrote a dissertation "On the Psychology and Pathology of the So-called Occult Phenomena", which turned out to be a prelude to his creative period that lasted almost sixty years. Based on carefully prepared seances with her extraordinarily psychic cousin Helen Preiswerk, Jung's work presented a description of her messages received in a mediumistic trance. It is important to note that from the very beginning of his professional career, Jung was interested in the unconscious mental products and their meaning for the subject. Already in this study / 1- Vol. 1. S. 1-84; 2- С.225-330 / can be easily seen logical basis of all his subsequent works in their development - from the theory of complexes to archetypes, from the content of libido to the concept of synchronicity, etc.

In 1900, Jung moved to Zurich and began working as an assistant for the then famous psychiatrist Eugene Bleuler at the Burchholzli hospital for the mentally ill (a suburb of Zurich). He settled on the hospital grounds, and from that moment on, the life of the young employee began to pass in the atmosphere of a psychiatric monastery. Bleuler was the visible embodiment of work and professional duty. He demanded accuracy, accuracy and attentiveness to patients from himself and his employees. The morning round ended at 8.30 am with a working meeting of the staff, at which messages about the condition of the patients were heard. Two or three times a week at 10.00 in the morning, doctors met with the obligatory discussion of the case histories of both old and newly admitted patients. The meetings took place with the indispensable participation of Bleuler himself. The obligatory evening round took place between five and seven o'clock in the evening. There were no secretaries, and the staff typed the medical histories themselves, so sometimes they had to work until eleven o'clock in the evening. The hospital gates and doors were closed at 10:00 pm. The junior staff did not have keys, so if Jung wanted to return home later from the city, he had to ask one of the senior staff for the key. Prohibition reigned on the hospital grounds. Jung mentions that he spent the first six months completely cut off from the outside world and in free time read the fifty-volume Allgemeine Zeitschrift fur Psychiatrie.

Soon he began to publish his first clinical works, as well as articles on the application of the test of word associations he had developed. Jung came to the conclusion that through verbal connections it is possible to detect ("grope") specific populations(constellations) of sensually colored (or emotionally "charged") thoughts, concepts, representations and, thereby, give an opportunity to reveal painful symptoms. The test worked by assessing the patient's response in terms of the time lag between stimulus and response. As a result, a correspondence was revealed between the word-reaction and the subject's behavior itself. A significant deviation from the norms marked the presence of affective-loaded unconscious ideas, and Jung introduced the concept of "complex" to describe their whole combination. / 3- С.40 ff. /

Freud's works, despite their controversial nature, inspired a group of leading scientists of the time to work with him in Vienna. Some of these scientists eventually moved away from psychoanalysis in order to look for new approaches to understanding the person. Carl Gustav Jung was the most prominent defector from the Freudian camp.

Like Freud, K. Jung devoted himself to the teaching of dynamic unconscious drives for human behavior and experience. However, unlike the first, Jung argued that the content of the unconscious is more than repressed sexual and aggressive urges. According to Jung's theory of personality known as analytical psychology, individuals are motivated by intrapsychic forces by images that have their origins in evolutionary history. This innate unconscious contains deep-rooted spiritual material that explains the inherent desire of all of humanity for creative expression and physical perfection.

Another source of controversy between Freud and Jung is the relationship to sexuality as the dominant force in the structure of personality. Freud interpreted libido mainly as sexual energy, while Jung saw it as a diffuse creative life force, manifesting itself in a variety of ways, such as in religion or the desire for power. That is, in Jung's understanding, libido energy is concentrated in various needs - biological or spiritual - as they arise.

Jung argued that soul(in Jung's theory, a term analogous to personality) consists of three separate but interacting structures: the ego, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious.

Ego

Ego is the center of the sphere of consciousness. It is a psyche component that includes all those thoughts, feelings, memories and sensations, thanks to which we feel our integrity, constancy and perceive ourselves as people. This serves as the basis of our self-awareness, and thanks to it we are able to see the results of our normal conscious activities.

Personal unconscious

Personal unconscious contains conflicts and memories that were once realized, but now suppressed or forgotten. It also includes those sensory impressions that lack brightness in order to be noted in consciousness. Thus, Jung's concept of the personal unconscious is somewhat similar to Freud's. However, Jung went further than Freud, emphasizing that the personal unconscious contains in itself complexes, or an accumulation of emotionally charged thoughts, feelings and memories taken by an individual from his past personal experience or from ancestral, hereditary experience. According to Jung, these complexes, arranged around the most common topics, can have a fairly strong influence on the behavior of an individual. For example, a person with a power complex can spend a significant amount of psychic energy on activities directly or symbolically related to the topic of power. The same can be true of a person who is under the strong influence of a mother, father, or under the rule of money, sex, or some other kind of complexes. Once formed, the complex begins to influence the behavior of a person and his attitude. Jung argued that the material of the personal unconscious in each of us is unique and, as a rule, available for comprehension. As a result, the components of the complex, or even the entire complex, can be realized and exert an excessively strong influence on the life of the individual.

Collective unconscious

And, finally, Jung expressed the idea of the existence of a deeper layer in the structure of the personality, which he called collective unconscious... The collective unconscious is a repository of latent traces of the memory of humanity and even our humanoid ancestors. It reflects thoughts and feelings that are common to all human beings and are the result of our shared emotional past. As Jung himself said, “the collective unconscious contains all the spiritual heritage of human evolution, reborn in the structure of the brain of each individual”. Thus, the content of the collective unconscious is formed due to heredity and is the same for all mankind. It is important to note that the concept of the collective unconscious was the main reason for the divergence between Jung and Freud.

Archetypes

Jung hypothesized that the collective unconscious consists of powerful primary mental images, the so-called archetypes(literally, “primary models”). Archetypes are innate ideas or memories that predispose people to perceive, experience, and respond to events in a certain way. In reality, these are not memories or images as such, but rather, precisely the predisposing factors under the influence of which people implement in their behavior universal models of perception, thinking and actions in response to an object or event. Inherent here is precisely the tendency to react emotionally, cognitively and behaviorally to specific situations - for example, in an unexpected encounter with a parent, a loved one, a stranger, with a snake or death.

Among the many archetypes described by Jung are mother, child, hero, sage, sun deity, rogue, God and death.

Examples of archetypes described by Jung|

Definition |

||

|

The unconscious female side of a man's personality |

Woman, Virgin Mary, Mona Lisa |

|

|

The unconscious male side of a woman's personality |

Man, Jesus Christ, Don Juan |

|

|

Human social role arising from social expectations and early learning |

||

|

The unconscious opposite of what the individual insists on in consciousness |

Satan, Hitler, Hussein |

|

|

The embodiment of integrity and harmony, the regulating center of the personality |

||

|

Personification of life wisdom and maturity |

||

|

The ultimate realization of psychic reality projected onto the outside world |

Solar eye |

Jung believed that each archetype is associated with a tendency to express a certain type of feeling and thought in relation to the corresponding object or situation. For example, in the child's perception of his mother, there are aspects of her actual characteristics, colored by unconscious ideas about such archetypal maternal attributes as upbringing, fertility and dependence.

Further, Jung assumed that archetypal images and ideas are often reflected in dreams, and are also often found in culture in the form of symbols used in painting, literature, and religion. In particular, he emphasized that the symbols characteristic of different cultures often show striking similarities, because they go back to the archetypes common to all mankind. For example, in many cultures he has seen images mandalas, which are symbolic embodiments of the unity and integrity of the "I". Jung believed that understanding archetypal symbols aided him in analyzing the patient's dreams.

The number of archetypes in the collective unconscious can be unlimited. However, Jung's theoretical system focuses on the persona, anime and animus, shadow and self.

A person

A person(from the Latin word “persona”, meaning “mask”) is our public face, that is, how we manifest ourselves in relations with other people. The persona denotes the many roles that we play in accordance with social requirements. In Jung's understanding, a persona serves the purpose of impressing others or concealing his true identity from others. The person as an archetype is necessary for us to get along with other people in Everyday life... However, Jung warned that if this archetype acquires great importance, then a person may become shallow, superficial, reduced to only one role and alienated from true emotional experience.

Shadow

In contrast to the role that the person plays in our adaptation to the world around us, the archetype shadow represents the suppressed dark, evil and animal side of the personality. The shadow contains our socially unacceptable sexual and aggressive impulses, immoral thoughts and passions. But the shadow also has positive aspects. Jung viewed the shadow as a source vitality, spontaneity and creativity in the life of an individual. According to Jung, the function of this is to channel the energy of the shadow in the right direction, to curb the harmful side of our nature to such an extent that we can live in harmony with others, but at the same time openly express our impulses and enjoy a healthy and creative life.

Anima and Animus

The anima and animus archetypes express Jung's recognition of the innate androgynous nature of humans. Anima represents the inner image of a woman in a man, his unconscious feminine side; while animus- the inner image of a man in a woman, her unconscious masculine side. These archetypes are based, at least in part, on the biological fact that both male and female hormones are produced in the body of a man and a woman. This archetype, Jung believed, evolved over the centuries in the collective unconscious as a result of the experience of interaction with the opposite sex. Many men have become “feminized” to some extent as a result of living together with women for many years, and the opposite is true for women. Jung insisted that anima and animus, like all other archetypes, should be expressed harmoniously, without disturbing the overall balance, so as not to hinder the development of the personality in the direction of self-realization. In other words, a man should express his feminine qualities along with masculine ones, and a woman should show her masculine qualities, as well as feminine ones. If these necessary attributes remain undeveloped, the result will be one-sided growth and personality functioning.

Self

Self Is the most important archetype in Jung's theory. The self is the core of the personality around which all other elements are organized.

When the integration of all aspects of the soul is achieved, a person feels unity, harmony and integrity. Thus, in Jung's understanding, the development of the self is the main goal of human life. The main symbol of the archetype of self is the mandala and its many varieties (abstract circle, saint's halo, rosette window). According to Jung, the integrity and unity of the “I”, symbolically expressed in the completeness of figures, like a mandala, can be found in dreams, fantasies, myths, in religious and mystical experience. Jung believed that religion is great power, contributing to the desire of a person for integrity and completeness. At the same time, the harmonization of all parts of the soul is a complex process. True balance of personality structures, as he believed, cannot be achieved, at least, this can be achieved not earlier than middle age. Moreover, the archetype of the Self is not realized until the integration and harmony of all aspects of the soul, conscious and unconscious, occurs. Therefore, reaching a mature “I” requires constancy, perseverance, intelligence and a lot of life experience.

Introverts and extroverts

Jung's most famous contribution to psychology is considered to be the two main directions, or life attitudes, described by him: extraversion and introversion.

According to Jung's theory, both orientations coexist in a person at the same time, but one of them becomes dominant. In the extraverted attitude, the focus of interest in the outside world - other people and objects, is manifested. The extrovert is mobile, talkative, quickly establishes relationships and attachments, external factors are the driving force for him. An introvert, on the other hand, is immersed in the inner world of his thoughts, feelings and experiences. He is contemplative, restrained, seeks solitude, tends to move away from objects, his interest is focused on himself. According to Jung, the extroverted and introverted attitude does not exist in isolation. Usually they are both present and are in opposition to each other: if one appears as a leader, the other acts as an auxiliary. The combination of leading and auxiliary ego orientations results in individuals whose behavior patterns are defined and predictable.

Soon after Jung formulated the concept of extraversion and introversion, he came to the conclusion that with the help of these opposing orientations it is impossible to fully explain all the differences in people's attitudes towards the world. Therefore, he expanded his typology to include psychological functions. Four main functions allocated by him is thinking, feeling, feeling and intuition.

Thinking and Feeling

Thinking and feeling Jung classified as rational functions, since they allow you to form judgments about life experience. The thinking type judges the value of certain things using logic and arguments. The opposite function of thinking - feeling - informs us about reality in the language of positive or negative emotions. The feeling type focuses on the emotional side of life experience and judges the values of things in terms of “good or bad,” “pleasant or unpleasant,” “prompts something, or cries out boredom.” According to Jung, when thinking acts as a leading function, the personality is focused on building rational judgments, the purpose of which is to determine whether the evaluated experience is true or false. And when the leading function is feeling, the person is focused on making judgments about whether the experience is, first of all, pleasant or unpleasant.

Feeling and intuition

The second pair of opposite functions - sensation and intuition - Jung called irrational, because they simply passively “grasp”, register events in the external or internal world, without evaluating them and explaining their meaning. Feeling is a direct, non-judgmental realistic perception of the world. The sensing type is especially keen on taste, smell, and other sensations from stimuli from the outside world. On the contrary, intuition is characterized by a subliminal and unconscious perception of current experience. The intuitive type relies on premonitions and guesses, grasping the essence of life events. Jung argued that when the leading function is sensation, a person comprehends reality in the language of phenomena, as if he were photographing it. On the other hand, when the leading function is intuition, a person reacts to unconscious images, symbols and the hidden meaning of the experience.

Each person is endowed with all four psychological functions. However, as soon as one personality orientation is usually dominant, likewise, only one function from a rational or irrational pair usually predominates and is recognized. Other functions are immersed in the unconscious and play an auxiliary role in the regulation of human behavior. Any function can be leading. Accordingly, the thinking, feeling, sensing and intuitive types of individuals are observed. According to Jung's theory, the integrated personality uses all the opposite functions to cope with life situations.

Two ego orientations and four psychological functions interact to form eight different types personality. For example, the extraverted thinking type focuses on objective, practical facts of the surrounding world. He usually comes across as a cold and dogmatic person living by established rules.

It is possible that the prototype of the extraverted thinking type was S. Freud... The introverted intuitive type, on the contrary, focuses on the reality of his own inner world. This type is usually eccentric, keeping away from others. In this case, Jung probably had himself in mind as a prototype.

Unlike Freud, who gave special attention to early years life as a decisive stage in the formation of models of personality behavior, Jung considered personality development as a dynamic process, as evolution throughout life. He said almost nothing about socialization in childhood and did not share Freud's views that only past events (especially psychosexual conflicts) are determining for human behavior.

From Jung's point of view, a person is constantly acquiring new skills, achieving new goals, realizing himself more and more fully. He attached great importance to such a life goal of the individual as "gaining selfhood", which is the result of the striving of all components of the personality for unity. This theme of the desire for integration, harmony and integrity was later repeated in the existential and humanistic theories of personality.

According to Jung, ultimate life goal- this is the complete realization of the “I”, that is, the formation of a single, unique and integral individual. The development of each person in this direction is unique, it continues throughout life and includes a process called individuation. Simply put, individuation is a dynamic and evolving process of integrating many opposing intrapersonal forces and tendencies. In its final expression, individuation presupposes the conscious realization by a person of his unique psychic reality, the full development and expression of all elements of the personality. The archetype of the self becomes the center of the personality and balances many opposing qualities that make up the personality as a single main whole. This releases the energy needed for continued personal growth. The result of the realization of individuation, which is very difficult to achieve, Jung called self-realization. He believed that this final stage of personality development is available only to capable and highly educated people who have sufficient leisure for this. Because of these limitations, self-realization is not available to the vast majority of people.

Jung is a very mysterious person in the scientific world, his ideas still excite the minds of his contemporaries. Jung expanded the boundaries of psychiatry, many of his theories were simply shocking to the ossified scientific community. In addition to scientific papers, Carl Jung read many theological and esoteric treatises. An unusual scientist showed great interest in folk tales and legends. Psychology owes many discoveries to Jung that formed the basis of modern knowledge about the human mind.

Jung. Psychological types

One of the most significant achievements of Carl Jung is his work on psychological types. In it, he puts forward the idea that, in addition to acquired qualities, a person has certain innate features of the psyche that cannot be changed. In many ways, this discovery was facilitated by the scientist's observation of young children who had not yet had time to acquire certain character traits, but there were serious differences in their behavior.

On the basis of these differences, psychological types were identified. Jung, on the basis of numerous experiments and observations, realized that some people give their energy outward, they are focused only on the world around them, people or objects outside arouse in them much more interest than the psychologist called such people extroverts. The other type, on the contrary, starts from his view of the world, and not from the objective environment, inner experiences interest these subjects more than people and objects from the external world. Carl Jung called them introverts. Let's take a closer look at these psychological types.

Extroverts

Modern society is just a paradise for extroverts, because it welcomes arrogance, superficiality, materialism and selfishness. But who are the extroverts? According to Jung's concept, it is a psychological type of a person directed purely outward. Such people adore the company of other people, they naturally defend their interests and strive for leadership.

They can be outgoing, benevolent and kind, but it is also easy to deal with hysterical and angry people.

An extrovert can be the life of a company, a leader in a movement or organization, thanks to her excellent communication skills and organizational talents. However, extroverts find it extremely difficult to immerse themselves in their inner world, so they are very superficial.

Strengths and weaknesses of extroverts

Each psychological type has its own strengths and weaknesses. For example, extroverts are great at adapting to a change of environment, they can easily find in any team. Jung's concept of psychological types describes extroverts as excellent conversationalists, capable of engaging in conversation anyone who is around them.

Also, such people can be great salesmen or managers, they are easy-going and mobile. Generally speaking, extroverts are ideally suited to living in today's shallow society of nosy materialists.

But not everything is so cloudless in the fast-paced world of extroverts. According to Jung's psychological types, each of them has its disadvantages. For example, extroverts are too dependent on public opinion, their worldview is based on generally accepted dogmas and concepts. They also often commit rash actions and deeds that they later regret. Superficiality creeps into all spheres of the extrovert's life, recognition in society and official awards attract them more than real achievements.

Introverts

According to Jung's concept, the psychological type of a person, directed inward, is called an introvert. It is not easy for introverts to find their place in the modern, fast-paced and hyperactive world. These people draw joy from within themselves, not from the outside, like extroverts. The outside world is perceived by them through a layer of their own inferences and concepts. An introvert can be a deep and harmonious person, but more often than not, such people are typical losers who are slovenly dressed and have difficulty finding a common language with others.

It might seem horrible to be an introvert, but according to the works of Carl Gustav Jung, psychological types cannot be good or bad, they are just different. Introverts not only have weaknesses, they also have their own strengths.

Strengths and weaknesses of introverts

Introverts, despite all the difficulties they experience in everyday life, have a number of positive characteristics. For example, introverts are capable of being good specialists in complex fields, brilliant artists, musicians.

It is also difficult for such people to impose their opinions, they do not lend themselves well to propaganda. An introvert is able to penetrate deep into things, calculate the situation many moves ahead.

However, society does not need smart or talented people, it needs arrogant and active hucksters, so introverts today are assigned a secondary role. The passivity of introverts often turns them into a jelly-like inert mass that sluggishly flows along the path of life. Such people are completely unable to stand up for themselves, they simply experience resentment inside, falling into another depression.

Functions of consciousness

Describing psychological types, Jung singled out four functions of consciousness, which, when combined with the orientation of a person inward or outward, form eight combinations. These functions differ significantly from other psychological processes, therefore they were singled out separately - thinking, feeling, sensation, intuition.

By thinking, Jung understood intellectual and logical Feeling - a subjective assessment of the world based on internal processes. By sensation is meant the perception of the world with the help of A, and by intuition, the perception of the world based on unconscious signals. To better understand Jung's psychological types, let's take a closer look at the functions of the psyche.

Thinking

The mental types based on thinking are divided into introverted and extroverted. The extraverted thinking type bases all its judgments on intellectual conclusions about the surrounding reality. His picture of the world is completely subordinated to logical chains and rational arguments.

Such a person believes that the whole world should obey his intellectual scheme. Anything that does not obey this scheme is wrong and irrational. Sometimes these people are useful, but more often they are simply unbearable for others.

As follows from the works of Carl Gustav Jung, psychological types of the introverted-thinking type are almost the exact opposite of their extroverted counterparts. Their picture of the world is also based on intellectual fabrications, but they are based not on a rational picture of the world, but on its subjective model. Therefore, this psychological type has many ideas that are completely natural for him, but have no connection with the real world.

Feeling

The extraverted feeling type, as Carl Jung's psychological types say, bases his life on feeling. Therefore, thought processes, if they contradict feeling, are discarded by such an individual, he considers them unnecessary. Feelings of the extraverted type are based on generally accepted stereotypes about the beautiful or the right. Such people feel what is accepted in society, although at the same time they are completely sincere.

The introverted feeling type comes from subjective feelings that are often understandable only to him. The true motives of such a person are usually hidden from outside observers, often people of this type look cold and indifferent. Quiet and benevolent in appearance, they can hide completely inadequate sensory experiences.

Sensation

The feeling extraverted type perceives the surrounding reality more sharply than other psychological types. Jung described this type as a person living in the here and now.

He wants the most intense sensations, even if they are negative. The picture of the world of such a subject is built on observations of objects of the external world, which gives sensing extraverts a touch of objectivity and prudence, although in reality this is not at all the case.

The introverted feeling type is extremely difficult to understand. The main role in the perception of the world for this psychological type is played by its subjective reaction to the world. Therefore, the behavior of sentient introverts can be incomprehensible, illogical, and even intimidating.

Intuition

The intuitive type is one of the most incomprehensible and mysterious. Carl Jung's other psychological types are more rational, with the exception of the sentient. If the intuitive type manifests itself in an extrovert, then a person arises who is constantly looking for opportunities, but as soon as the opportunity is studied and clear, he abandons it for further wanderings. Such people make good businessmen or producers. They are said to have excellent instincts.

However, the intuitive type combined with introversion makes the strangest combination. Describing psychological types, Jung noted that intuitive introverts can be great artists and creators, but their work is unearthly, bizarre. In communicating with such a person, a lot of difficulties can arise, since often he expresses his thoughts only to him in one understandable way. People of this kind are fixated on perception and its description. If they do not find an outlet for their feelings in creativity, then it becomes difficult for them to take their place in society.

Can you change your psychological type?

Psychological types do not occur in their pure form. Every person has both an extrovert and an introvert, but one of these types is dominant.

The same is true with the functions of consciousness, that is, if you have a feeling type in front of you, this does not mean at all that he does not use the intellect, it is just that feelings play a decisive role in his life. According to Jung's concept, the psychological type of a person remains unchanged throughout his life. However, it can be slightly adjusted, subject to external circumstances.

If you are not satisfied with your psychological type, do not be discouraged or try to fight your nature. It is much wiser to build a competent life strategy that will take into account your strengths and weaknesses. Despite the fact that the dominant type cannot be changed, this does not mean that it is impossible to somehow change. Most of the features human character are not innate and unchanging. Moreover, psychology is not physics, it only suggests, and does not assert, so that everything is in your hands. Those who want to learn more about this topic can read a wonderful book - Jung K.G. "Psychological types".