History in Istanbul looks at you from almost every stone. So the walk drew my attention to this historical figure. The personality turned out to be curious and ambiguous.

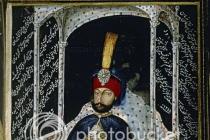

Mahmud II was 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Nice number, isn't it? :)

And the son of a woman who is persistently attributed to being related (almost a cousin) to Napoleon’s wife Josephine. In the harem her name was Nakshidil. But the true name is supposedly Aime de Riveri. Well, you remember, right? :)

She was born, they say, in the Caribbean, on the island of Martinique, and then the ship she was sailing on was captured by Berber pirates, who sold her to Algeria, from where she later ended up in the harem of Sultan Abdul-Hamid I, becoming his fourth wife and Mahmud’s mother II:

Mahmud II reigned for 31 years at the beginning of the 19th century - from 1808 to 1839. And in theory, he might not have become a sultan at all. Before him, the Sultan was Selim III, who was overthrown from the throne in 1807 by the rebel Janissaries, dissatisfied with the ruler’s reforms. Mustafa IV, the elder brother of Mahmud II, was placed on the throne. But the deposed Selim III had his own supporters, who, having gathered their strength a year later, tried to return him to the throne by starting a rebellion. While they were storming the palace, the ruling Mustafa IV, don’t be a fool, ordered the death of Selim, and at the same time his younger brother Mahmud II. Selim was strangled, and Mahmud managed to dodge the killers, like Santa Claus, jumping out of the chimney onto the roof. By that time, the rebels had already captured the palace and Sultan Mustafa. And then it turned out that since Selim III was killed, the only one from the Ottoman dynasty who could inherit the throne was Mahmud II. By the way, a couple of months later he took revenge on his brother, who ordered his death, in a similar way. Intrigue-intrigue!...

It is curious that those who elevated the new sultan to the throne subsequently died at his own “hand.” It was Mahmud II who put an end to the legendary army of the Janissaries of the Ottoman Empire in 1826:

When I read about Mahmud II (Konstantin Ryzhov’s essay “Sultan Mahmud II”), the first thing that came to mind was a comparison with Peter I. His reforms are very reminiscent of Peter’s. Judge for yourself:

“Mahmoud practiced sending young Turks to study abroad. State reforms took place against the background of the general Europeanization of life. During the reign of Mahmud, the first Turkish newspaper began to be published, many printed books appeared, and many European things came into use, including chairs and clocks. The suit has become Europeanized. An example of this was set by the Sultan himself, who on Ramadan 1828 appeared before the people in blue trousers and a red uniform. Special decrees regulated the cut of men's and women's dresses, as well as the length of beards. Turkish dignitaries began to attend balls and receptions organized by foreign embassies, sitting there at the same table with Europeans and ladies, which was previously considered completely unacceptable.”

However, Mahmud II still did not reach Peter I. The Ottoman Empire weakened under him, suffered defeats in wars... As his military adviser, the famous Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, later wrote, “He (Mahmud II) was never able to achieve the goal that he had strived for all his life. Rivers of blood were shed, the old institutions and sacred traditions of the country were destroyed. For the sake of reforms, the faith and pride of his people were undermined, and these reforms were compromised by all the events that followed.”

The Sultan died in 1839 from pulmonary tuberculosis and cirrhosis of the liver, which, you know what happens. :)

Now rests behind high walls:

By the way, Mahmud II’s successor was Abdulmejit I, his eldest son. The same one with whom we are already a little familiar thanks to.

Unfortunately, we didn’t get to the Sultan’s tomb in the cemetery; it was closed for restoration:

I had to be content with her review:

From different sides:

However, this did not upset us at all and we had a wonderful walk through the lovely, quite romantic and not at all gothic cemetery. :)

It’s probably not scary to come to something like this even at night. :)

Since we came to this cemetery by accident, I was not prepared informationally. So I just took pictures of what I saw around:

And I didn’t know that here, in this tomb, rested the Sultan’s elder sister Esma, his wife Bezmiyalem Valide Sultan, his son and grandson, who also later became sultans, - Abdulaziz II(pictured right) and Abdulhamit II(pictured left):

In the cemetery itself are the last branches of the dynasty that lost power:

Granddaughter of Sultan Murad V Emine Atiye Sultan, last grandson of Sultan Abdulhamid II Osman Ertugrul(Osman Ertuğrul), born during the reign of the Ottoman dynasty (1912) Lived 97 years! Mashallah! - as the Turks say! And he died quite recently - in 2009. Would have been a sultan if Atatürk had not founded the Turkish Republic:

At the time of its proclamation, Osman was studying in Vienna. He remained there until 1939, after which he moved to New York. The descendants of the sultans were forbidden to enter the country for a long time. And when, finally, the government warmed up to the disgraced royals and itself invited Osman to visit his historical homeland, the modest Sultan, like an ordinary tourist, stood in line to see, in fact, his own home, where he spent his childhood - Dolmabahce Palace. But he still rested in Istanbul. May he rest in peace!

Turkish Sultan from the Ottoman dynasty, who reigned from 1808 to 1839. Son. Abdul-Hamid I. Born. July 20, 1785 + July 1, 1839

Mahmud became the Sultan almost by accident: he was enthroned by participants in the coup on July 28, 1808, led by Mustafa Pasha Bayraktar. By besieging the Sultan's palace, they were going to return power to Sultan Selim III, who had been deposed a year before. However, he was strangled by order of Mustafa IV, Mahmud's elder brother. Mahmud himself almost shared the fate of the unfortunate man - the killers were already chasing him, but people loyal to the prince helped him get out through the chimney onto the roof of the palace. After the deposition of Mustafa IV, Mahmud remained the last scion of the Ottoman dynasty. Bayrakrat had no choice but to proclaim him Sultan. In turn, Mahmud had to appoint Bayrakrat as grand vizier and transfer all power into his hands. First of all, he brought down his anger on the favorites of Mustafa IV and the Yamacs, who played a sinister role in the overthrow of Selim III. In the very first days of his viziership, he executed 300 people (among them was Musa Pasha, who actually led the coup of 1807). The Yamak detachments were deprived of their salaries and dispersed. Then Bayrakrat brought order to the capital with harsh measures. Istanbul, which during the entire reign of Mustafa IV was at the mercy of unbridled gangs of Janissaries and Yamaks, finally calmed down. But the main goal of the organizers of the 1808 coup was to return to the policy of Selim’s reforms, as a result of which it was planned to create a large, regular army trained in the European style in Turkey.

Already in October, Bayrakrat decided to form a regular corps of secbans (the so-called Janissary riflemen) numbering 5 thousand people. Formally, the Sekbans were supposed to form the eighth center of the Janissary army, but in fact they were the first detachment of the regular army. This innovation could not help but irritate the Janissaries, who saw their competitors in the secbans. At court they treated him just as coldly. Mahmud, deprived of real power, looked at Bayrakrat as a usurper and dreamed of putting an end to him. However, deliverance from the all-powerful vizier did not come to Mahmud at all as he had expected. The enemies of reform, defeated in July, went on the offensive in November. The uprising began on the night of November 14-15. A detachment of 1,000 Janissaries surrounded Bayrakrat's house and began a battle with his people. When all possibilities for defense were exhausted, Bayrakrat blew up a powder magazine in the basement of his tower. More than 300 Janissaries died under its rubble. Many of Bayrakrat's associates were killed. The Janissaries wanted to restore Mustafa IV to the throne and began a siege of the Sultan's palace. But Mustafa was killed on the orders of Mahmud. Now he remained the only offspring of the Ottoman dynasty. The rebellion against him lost all meaning and peace was concluded on November 17. Mahmud agreed to execute Bayrakrat’s closest associates and destroy the “new army” - the corps of sekbans. In response, the Janissaries agreed to consider him their sultan.

It seemed that the idea of military reform was buried forever. However, the objective course of events forced the Sultan to return to her again and again. The reason for this was external and internal wars, in which the Turkish army with sad consistency demonstrated its complete insolvency. The beginning of Mahmud's reign was marked by another Russian-Turkish war. At first, it progressed sluggishly, since both states had no time for it. Then hostilities intensified. In the fall of 1811, Kutuzov inflicted a heavy defeat on the Turks near Rushchuk. The Sultan's Danube army was defeated and he was forced to begin peace negotiations. Under the Treaty of Bucharest, Türkiye ceded Bessarabia to Russia. The Serbs, who actively fought on the side of the Russians, received autonomy. However, Russia was unable to defend the interests of its allies because of the outbreak of the war with Napoleon. Immediately after the signing of the Treaty of Bucharest, Mahmud began preparing a campaign against Serbia. By the beginning of summer, three armies with a total number of 250 thousand people were concentrated on its borders. In July, heavy fighting broke out along the entire Serbian-Turkish border. The Serbian rebels, who were five times smaller than the Turks, could not resist such a strong enemy. By October they were defeated on all fronts. The leader of the uprising, Kara-George, fled to Austria. On October 7, the Turks entered Belgrade. A wild orgy of reprisals, murders, enslavement and robberies of civilians began. The Serbs were demanded to pay taxes for all the years of the uprising, starting from 1804. Unable to tolerate the terror of the Turkish authorities, the Serbs again took up arms in April 1815. Soon the forces of the rebels already amounted to 40 thousand people. Mahmud realized that Serbia could not be held back by repressive measures alone and, through the mediation of Russia, he concluded an agreement with the leader of the uprising, Milos Obrenovic. According to its terms, Serbia received minor autonomy. But the national movement in the Ottoman provinces did not stop there. In the early 20s. the uprising swept Wallachia. Then the Greek liberation war began.

This last uprising was prepared by members of the secret society "Filiku Eteria", led by the Russian service general Ypsilanti. (The society was founded in 1814 in Odessa. Since 1818, the center of the organization moved to Istanbul. There were etherist branches in many cities of the Balkan Peninsula). The uprising began in April 1821 in Morea and in a short time spread to all of continental Greece, the islands of the Aegean and Andriatic seas. The moment chosen for him turned out to be very favorable, since at that time the Sultan was waging a stubborn war with the Vali of Yanina Pashalyk Ali Pasha of Yaninsky, who created, in fact, an independent appanage principality. The government troops directed against Ali Pasha also included the garrisons of many cities of Morea, which facilitated the implementation of the plans of the Eterists. The rebels occupied Patra, Corinth, Argos and a number of other cities. They were soon joined by residents of the larger islands.

Mahmud reacted to the news of the uprising very painfully. Messengers were sent to all parts of the empire to inform the Muslims that the throne was in danger and to urge everyone who was able to bear arms to hurry to Istanbul. Mahmud then proclaimed a “holy war against the infidels.” The first victim of this call was the Christian population of the capital, most of whom had nothing to do with the uprising. Over the course of several weeks, Muslim fanatics killed more than 10 thousand Christians in Istanbul (including Patriarch Gregory of Constantinople, who was hanged on the gates of the patriarchal house). Then a wave of Christian pogroms took place throughout the empire, which resulted in countless new victims (for example, on Chios, the Turks killed and sold into slavery 70 thousand people - almost its entire Christian population). In response to these atrocities, Greece began to massacre Muslims. Many Greeks, previously far from the liberation struggle, took up arms. In October 1821, after a five-month siege, the rebels captured the administrative center of the Morea, Tripolis. By the beginning of 1822, they were already masters of the entire peninsula, a significant part of central Greece and a number of Greek islands. In January 1822, the National Assembly was convened in Epidaurus, which proclaimed the independence of Greece and adopted its constitution. After this, the uprising spread to several areas of Thessaly and Macedonia.

In the spring, the Sultan moved the army of Dramali Mahmud Pasha against the Greeks. At the beginning of July 1822, through the Isthmus of Corinth, she invaded Morea, occupied Argos, but was unable to develop her success. The power of the Turks turned out to be powerless against the actions of countless partisan detachments, which inflicted terrible damage on Mahmud Pasha in many small battles. There was an urgent need to find reserves, but just at that time the war with Iran began, which drew upon significant forces of the Turkish army. Having no other options to deal with the uprising, the Sultan turned for help to his vassal, the ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali. He provided Mahmud with a European-trained army and a fairly modern fleet to fight the Greek rebels, but in return demanded that Morea be transferred to the control of his son Ibrahim. The Sultan agreed. The arrival of Ibrahim Pasha's troops changed the situation dramatically. In November 1824, he defeated the uprising in Crete, in February 1825 he captured Navarino, in the summer of the same year he captured a significant part of Morea, and in June he took Tripolis.

The successes of the Egyptian army, its high combat effectiveness and good training convinced Mahmud that it was necessary to return to the reforms of Selim III and immediately begin the reorganization of the Turkish army. Many of his close associates were inclined to do the same. In May 1826, the highest secular and spiritual dignitaries of the empire discussed and approved a plan for the creation of a new regular Ishkenji corps, numbering 7.5 thousand people. The salary for his soldiers was set at 8 times higher than the Janissary salary. On May 29, Mahmud signed a corresponding decree. Within a few days, more than 5 thousand people signed up for the corps. On June 12, with a large crowd of people on Myasnaya Square, the first training sessions began with a group of soldiers of the new army. The Janissaries immediately sensed the threat posed by this initiative and on June 15 they launched an uprising in Istanbul. Having learned about the rebellion, the Sultan (he was then in his summer residence on the European shore of the Bosporus) immediately arrived at the Sultan's palace Topkau and began to suppress it. The main force for the fight against the Janissaries were artillery units, as well as bombardiers, miners and sailors. While the Janissaries rushed around Istanbul in blind rage and wasted time setting fire to the houses of hated dignitaries, plundering property and killing their loved ones, a large army was drawn to Topkau. The artillerymen alone - disciplined and European-trained soldiers - numbered 14 thousand.

Hearing about these preparations, the rebel Janissaries (there were about 15 thousand of them) gathered in the square and demanded that the Sultan cancel the decree on the formation of the Ishkenji army and hand over some of his dignitaries to them for reprisals. Mahmud flatly refused to comply with these demands and both sides prepared for battle. Public opinion was on Mahmud's side. Even the ulema, when asked by the Sultan what punishment the rebels who took up arms against their Sultan and Caliph deserve, gave a unanimous answer - death! It was decided to display the sacred banner of the prophet, kept in the Ottoman palace, at the Sultan Ahmad Mosque and call on the people to gather under it to punish the rebels. Residents of the capital did not remain indifferent to this call and everyone who wanted to take part in the battle was given weapons. The Sultan's troops surrounded Myasnaya Square, after which the rebels were asked to surrender. They refused, and immediately the artillerymen opened murderous fire on the crowd of Janissaries. The rebels retreated in disorder to their barracks, but the shelling pursued them here too. The wooden barracks caught fire. About 3 thousand Janissaries died in the flames. The artillerymen burst into the square and began to kill those who were still alive. Within five hours the rebellion was suppressed. The surviving Janissaries were grabbed on the streets, in courtyards, pulled out of hiding and either killed on the spot or sent to a specially created court. In total, at least 7 thousand Janissaries were killed, another 15 thousand were expelled from the capital. On June 17, 1826, a meeting of senior dignitaries decided to liquidate the Janissary corps. A decree was sent to the province dissolving all Janissary formations and executing the disobedient. It was performed with great zeal. As a result, about 30 thousand more Janissaries were executed locally. This type of army ceased to exist forever. Mahmud then liquidated the Yamak units and abolished the regular Sipahi cavalry. Both of these formations, like the Janissary corps, were a constant source of unrest and a stronghold of reaction. In August, the Sultan dissolved the Baktashi dervish order, with which the Janissary corps had had close ties for many centuries. The leaders of the order were publicly executed, and all the dervish monasteries were destroyed. After this, the creation of a regular army proceeded at an accelerated pace. In the summer of 1826, the Sultan issued a decree on the formation of new infantry units, the training of which was to be carried out according to European models. In total, it was planned to create eight regiments of the new army with a total number of 12 thousand people. French instructors were invited to train them.

The creation of a new army was only at the very beginning, when a new great external war began, caused by Greek events. In June 1827, Russia, France and England sent an ultimatum to Mahmud demanding autonomy for Greece. Mahmud refused to fulfill it. In August, an Anglo-Russian-French squadron approached the shores of the Morea. The Allies had 26 ships. They were opposed by a Turkish-Egyptian fleet of 65 ships. Nevertheless, the battle in Navarino Bay, which took place on October 20, 1827, ended in complete defeat for him - the Turks lost 55 ships, and the allies lost none. The position of Ibrahim Pasha’s army immediately deteriorated sharply after this. He was cut off from Egypt and had no opportunity to receive either ammunition or food. In 1828, at the request of the European powers, the Egyptians evacuated their army. In April of the same year, the Russian-Turkish war began. In May, the Russians crossed the Prut and invaded Moldavia. Russian ships began blockade of the Dardanelles. At the beginning of 1829, the Russian army crossed the Balkans and occupied Edirne on August 20. The threat looms over Istanbul itself. At the same time, Erzurum was captured in Transcaucasia. Mahmud had no choice but to accept the demands of the European powers. In September he signed a peace treaty. According to him, the mouth of the Danube and the eastern coast of the Black Sea passed to Russia. Greece and Serbia received autonomy. The majority of the Greeks and Serbs did not accept this compromise, and already at the beginning of 1830 the Sultan had to recognize the complete independence of Greece (without Thessaly and Epirus), and grant Serbia the status of an autonomous principality. This was the largest defeat of the Ottomans in history, demonstrating to the world how weak the Turkish Empire had become. In the same year, France began the conquest of Algeria, and the Egyptian Pasha Muhammad Ali openly broke away from the Sultan.

Mahmud was unable to repel French aggression, but he was not going to tolerate the insolence of the Egyptians. Since he did not have troops for an immediate war with Muhammad Ali, the Sultan pretended to maintain the most friendly relations with the Egyptian Pasha, and in the meantime carried out military reform at an accelerated pace. But Muhammad Ali did not allow him to gather his strength. In the fall of 1831, his army invaded Syria. Akka was taken in May 1832, and Damascus fell in June. In July, the Turks were defeated near Homs and in the Beilan Gorge. In November, the Egyptians passed the Cilician Gate, entered Anatolia, and in December occupied Konya. On December 20, a general battle took place near this city, and the Turkish army was again completely defeated. Mahmud lost almost all of his new regular regiments in this battle. The Grand Vizier who commanded them was captured. Therefore, in May 1833, the Sultan had to agree with the demands of Muhammad Ali and give Syria, Palestine and Cilicia under his rule. However, the Egyptian Pasha was still considered his vassal.

However, Mahmud viewed this agreement only as a temporary respite. He took up military reform with renewed energy. Despite the acute lack of funds and the population's dissatisfaction with recruitment, the size of the regular army was increased to 70 thousand people by 1836. At the same time, the restoration of the fleet was underway. Changes in the military sphere were accompanied by other transformations that affected all aspects of Turkish life. In 1834, an administrative reform was carried out, as a result of which the number of pashalyks increased, and their area decreased. Thus, the pashas lost the opportunity to accumulate significant forces in their hands and act as independent rulers. In addition, military power was taken away from them - it passed to the commanders of regular units. The central authorities did not go unnoticed. Ministries were created, and in 1837 Mahmud formed the Council of Ministers, to which executive power was transferred. The Grand Vizier began to be called the Prime Minister. New positions and titles were introduced, government salaries were established (before this, officials lived on the offerings of those who turned to them). Mahmud tried to fight bribery, but had little success. As a result of all these measures, the old feudal system of state bodies of the empire became somewhat Europeanized. The authority of the central government strengthened.

Like all reformer sovereigns, Mahmud faced an acute personnel problem. The state needed officers, military engineers, civil officials and specialists of various kinds - doctors, teachers, translators, etc. This problem was solved with great difficulty, since in Turkey there was no base for training such specialists - there were not even secular primary and secondary schools. The creation of the latter began with a decree of 1824, but progress was extremely slow. The Sultan paid the main attention to the training of officers. In 1834, he opened the Combined Arms Military School (the French College of Saint-Cyr was taken as a model, but Prussian officers predominated among the teachers here). At first, no one wanted to study at the school, and therefore an order was given for forced recruitment: teenagers were grabbed right on the streets of Istanbul, and then they were strictly monitored so that they did not run away. It is clear that this was not the best solution, and such cadets turned out to be of little use. In addition, the general educational level of the Turks was then so low that it was impossible to make good officers out of them in this way, even if one wanted to. The Sultan also showed a lot of attention to the training of doctors. In 1827 he opened a military medical school, and in 1829 a surgical school (however, only in 1838 was it possible to overcome the resistance of the clergy and allow practical training on corpses). In 1839, both medical schools were merged into the Sultan Higher Medical School. The School of Legal Education was founded for officials, and the School of Literary Sciences was founded for the training of translators. In addition, Mahmud practiced sending young Turks to study abroad. State reforms took place against the background of the general Europeanization of life. During the reign of Mahmud, the first Turkish newspaper began to be published, many printed books appeared, and many European things came into use, including chairs and clocks. The suit has become Europeanized. An example of this was set by the Sultan himself, who on Ramadan 1828 appeared before the people in blue trousers and a red uniform. Special decrees regulated the cut of men's and women's dresses, as well as the length of beards. Turkish dignitaries began to attend balls and receptions organized by foreign embassies, sitting there at the same table with Europeans and ladies, which was previously considered completely unacceptable.

This entire era bore the imprint of the personality of Sultan Mahmud. Outwardly unprepossessing, short in stature, he was a man of great intelligence, persistent in achieving his goals. Possessing a strong character and determination, he was at the same time very cautious and, when necessary, could hide his intentions for years. He was cruel and merciless towards his opponents. Executions under him were an ordinary and even ordinary occurrence. With all this, Mahmud was completely devoid of religious fanaticism and was keenly interested in European culture. Unfortunately, in the last years of his life, he became addicted to alcohol, as a result of which he began to get sick, the more severely he went on. In 1837-1839 he had long breaks when he could not engage in government affairs. Meanwhile, unrest and wars did not stop. In 1838, there was a new aggravation of relations with Muhammad Ali. The Sultan began to prepare for the war, which began in May 1839. Its outcome was the same as the first. On June 24, a decisive battle took place near Nisibin in Northern Syria. The Turkish army was completely defeated in it. Mahmud could not survive this defeat and died a few days after the news of it was received in Istanbul.

Participation in wars: Internecine wars. War with Yanina Pasha Ali. War with Muhammad Ali of Egypt. War with Russia (1806-1812). War with Russia (1828-1829).

Participation in battles:

(Mahmud II) Turkish Sultan (from 1808)

Enthroned on July 28 as a result of a coup d'état carried out by Mustafa Pasha Bayraktar in order to restore the “new system” Selima III. However, only in the mid-1820s, having strengthened their power and enlisted the support of influential dignitaries and high clergy, Mahmud II took the first steps towards overcoming feudal fragmentation, creating a centralized state apparatus and some “Europeanization” of the country.

The most important reforms of Mahmud II: the destruction of the Janissary corps in 1826, the establishment of European-style ministries and the introduction of a new administrative division with the deprivation of governors-general of the right to have their own army, the creation of several secular secondary schools and military schools.

Mahmud II led, although not always successfully, the struggle against the separatism of the outlying feudal lords.

Under Mahmud II, the national liberation movement of the Balkan peoples strengthened significantly, leading to the victory of the national revolution in Greece (1821-1829) and the autonomy of Serbia (1830).

In 1828-1829 Türkiye was defeated in the war with Russia and two armed conflicts with

The reformist policy of Selim 3 was continued by his successor Mahmud 2.

In May 1826, Mahmud issued a decree on the formation of a new army with the help of foreign officers. In June 1826, a rebellion of the Janissaries broke out. Mahmud was not taken by surprise, partly he himself forced the Janissaries to take rebellious actions in order to put an end to them. The reprisal was quick and bloody. The Janissaries gathered in their traditional gathering places - on the Hippodrome Square and on the Et-Meydan Square, and, turning over the cauldrons as a sign of rebellion, demanded the repeal of the decree on the formation of new troops. Immediately, artillery and other regular units emerged from the gates of the Sultan’s palace with the “banner of the prophet” (the sacred banner of the Ottomans) unfurled. The cannons fired directly at the crowded Janissaries, and those who fled were overtaken in their houses and barracks. The massacre continued for several days; tens of thousands of corpses were thrown into the Sea of Marmara and the Bosphorus. The massacre of the Janissaries also occurred in the provinces.

Subsequent reforms boiled down mainly to the following: the abolition of the military-feudal system (1834), the elimination of the most restrictive internal customs and a new administrative structure that made the rulers of the regions directly dependent on the Sultan. However, this applied only to those areas where the Sultan’s government had the support of Turkish landowners and had sufficient military coercive power. The outskirts still remained in the power of virtually independent rulers and governors

In the government, instead of the old positions, there were in 1836-1838. The posts of ministers of internal affairs, foreign affairs, and finance were established according to the European model. A military medical school was opened in Istanbul in 1826, and in 1832 the first newspaper in Turkish began to be published (“Diary of Incidents”),

The most important of the changes was the abolition of the military system. Tamara And zeamety turned into ordinary landholdings, not associated with military service and subject to land tax. But the reform was not completed. In a number of areas timariotes And loans, Having lost the right to corvée, they retained other feudal privileges, including the right to a third of the harvest. One of the most important obstacles to bourgeois-capitalist development still remained - the insecurity of private property. This also applied to the bourgeoisie. Mahmud II formally abolished the system of confiscation of property, but in reality arbitrariness continued. The Turkish and foreign (Greek, Armenian) trade and usurious bourgeoisie, which had accumulated money, could not invest it in industry.

An equally important obstacle to the development of its capitalism in Turkey was the increasing penetration of foreign capital. Mahmud II not only did not prevent this penetration, but also encouraged it. The reforms did very little in strengthening the Ottoman Empire, but at the same time contributed to the adaptation of the Turkish feudal system to the penetration of foreign capital and the further involvement of Turkey in the orbit of the world market.

In the 1830s, a widespread offensive by capitalist powers began in Asian markets. Meanwhile, Turkey, bound by the regime of capitulations, had no right to either increase duties or bring foreigners to trial, be it litigation with Turkish subjects or even crimes. In 1838, England forced the Porte to sign a trade convention, which established a low customs duty on goods imported into Turkey (5% of the value), prohibited the establishment of any monopolies, and allowed internal trade to foreigners in the empire. The convention specifically stipulated that its effect extended to the entire Ottoman Empire, including Egypt, where Muhammad Ali introduced state monopolies, protecting the country from capitulations. Also in 1838, a similar Franco-Turkish convention was signed.

The results were immediate. The Turkish handicraft industry has lost its last opportunity to compete with foreign goods imported at cheap prices.