Russian tea, Ivan-Chai or Koporsky tea – a drink known for over ten centuries. The tradition of tea drinking appeared in Russia long before acquaintance with overseas black tea. Dried leaves were used as tea leavesplants fireweed and this tea was in high esteem. According to Russian legend, fireweed was originally among the peopleIvan tea dignified ... “... There was one Russian boy, he always wore a red shirt and loved to be in the field among tall bushes and grasses. When people passed by and noticed something red among the greenery, they said: "Yes, it's Ivan, tea, wandering." And so it happened: the redness in the greenery was associated with Ivan ... ”. And once people made a fire and, together with firewood, threw tall grass of fireweed into the fire. Ivan-tea leaves got into a boiling cauldron, the broth turned out to be pleasantly fragrant, invigorated and understood the mood. And so it happened in Russiabrew.

This drink is mentioned in ancient Russian manuscripts, Europe knew and loved it, and therefore Ivan tea was exported in large quantities abroad, where it was called “Russian tea”. In the 19th century, Ivan tea was actively exported to Great Britain, which owned huge tea plantations in India, but annually bought tens of thousands of poods of Koporye tea, preferring it to Indian tea. But in the homeland of fireweed, in Russia at that time, the market was flooded with Indian tea and the healing national drink was undeservedly forgotten. But this primordially Russian aromatic, slightly tart drink is not only tasty, but also very useful for the whole organism.

Ivan tea is useful for a person with all its parts: salads are made from young shoots, the roots are eaten fresh, flour is made from dried ones. Ivan-tea fluff, which appears after flowering, is used for stuffing pillows. Fireweed is an excellent honey plant, from its nectar special fireweed honey, high-quality pollen is produced. From the stems of fireweed, fiber is obtained, but tea is made from inflorescences and leaves.

Koporsky tea has a pleasant, slightly tart taste with a fragrant floral-herbal aroma. Contains up to 20% tannins, bioflavonoids, mucus, pectin substances and vitamins of the "B", "C" group. Ivan-tea flowers contain up to 25 mg of nectar for each flower. In addition, Ivan tea contains a lot of protein, which is easily absorbed by the body, which allows you to simply and quickly be saturated with energy.

In 100 gr. green mass of Ivan-tea contains:

iron - 2.3 mg.

nickel - 1.3 mg.

copper - 2.3 mg.

manganese - 16 mg.

titanium - 1.3 mg.

molybdenum - 0.44 mg.

boron - 6 mg.

A significant amount of potassium, sodium, calcium, magnesium, lithium, etc. In 100 gr. Ivan tea leaves contain from 200 to 400 mg of ascorbic acid (several times more than in lemons). The presence of iron, copper, manganese in the plant allows us to consider it a means capable of improving the process of hematopoiesis, increasing the protective functions of the body. Does not contain caffeine, oxalic and uric acids, which are metabolic disorders.

There is no addiction to it, as to ordinary tea or coffee.

Has an effect: astringent and anti-inflammatory; analgesic and antipyretic; sedative for stress, nervous stress; removes food, alcohol poisoning, sobering; alkalizes, cleanses the blood; enhances immunity; restores strength when exhausted; useful for hypertension, atherosclerosis and anemia; useful for gout and salt metabolism disorders; ulcers of the gastrointestinal tract are healed; useful for stones in the liver, kidneys and spleen diseases; useful for internal bleeding, painful menstruation; strengthens hair roots; reduces intoxication in cancer; helps to get rid of prostatitis and prostate adenoma.

The composition determines the variety of healing properties of Ivan tea. Due to the high content of ascorbic acid and bioflavonoids (vitamin P), it is recommended to increase immunity and resistance to various infections, strengthen blood vessels, bind and remove heavy metals, cleanse the body with various intoxications, including alcoholic ones, from radiation pollution, heal and increase performance ... It has a beneficial effect on the immune and endocrine systems, is effective in any inflammatory process, has a pronounced soothing, mild hypnotic effect.

How to properly prepare and brew Ivan-Tea

How to properly prepare and brew Ivan-Tea

It will not be difficult to prepare Koporsky tea on your own, the main condition for preparation is to make fermentation ... As a result of this "operation", the insoluble useful substances of Ivan-tea pass into a soluble phase and can pass into water during brewing.

The plant itself contains everything you need for fermentation. These are his own juices and enzymes. If you crumple a leaf in your hands, then some of the cells will burst, the plant will let out juice. Wet crumpled leaves will contain vitamins, nutrients and intracellular enzymes. These enzymes, leaving the vacuoles, begin to actively change the biochemical composition of the plant. It's like self-digestion. At the same time, the leaves darken somewhat, a different, pleasant smell appears. For this fermentation process, it is necessary to leave finely cut, well-crumpled leaves in a non-metallic container under pressure (with a decrease in contact with air and metal, vitamins are preserved) for 1-2 days at room temperature. If you keep it longer, the tea will ferment like cabbage.

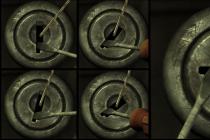

After fermentation, the leaves must be put in a cast-iron pan and simmer over very low heat for about forty minutes. This heating to a hot state is necessary to accelerate fermentation, in which part of the insoluble, non-extractable substances of plant tissue are converted into soluble and easily digestible substances. These are the substances that give the taste, smell and color of tea.

After forty minutes of simmering, you must turn on a medium heat and, constantly stirring with a wooden spatula, bring the leaves to a dry state. This must be done very carefully so as not to burn the leaves, otherwise the tea will take on a burnt aroma. In appearance, it is an ordinary black large-leaf tea, however, with a pleasant peculiar smell. When brewed, Ivan tea gives a good color and pleasant smell, and with an increase in dosage it acquires an intense color and astringency, similar to usual tea.

Interestingly, Ivan tea leaves do not stain the tooth enamel, and in general, properly prepared Ivan tea is much tastier than Indian or Ceylon tea. According to its properties, the Ivan-tea drink occupies, as it were, an intermediate position between black and green in strength and healing properties. And if you add flowers, dried berries and fruits to this tea, then it will become a true unique gift of Native Mother Nature - for your joy and surprise for your guests!

Fireweed - a wild plant growing near rivers, in moist soil. Also found in forest glades, hills, etc.It can grow up to half a meter, sometimes it reaches human height.It blooms almost throughout the summer with pinkish flowers that open only early in the morning.Plant-barometer - closes flowers before rain.

If you notice the Ivan-tea plantation, in the spring, around the beginning of May, cut off the tops of young shoots, from which you will get Koporsky tea of \u200b\u200bthe highest grade. And the cropped shoots will begin to bush, and by the beginning of flowering, there will be much more leaves on the plants than usual.

Raw materials are harvested during flowering, - July-August, when the flower cluster has not yet fully blossomed, because later, when the plant fades, fruit-boxes filled with seeds with down appear.

Tea got to Russia earlier than to Europe, but later than to the East. In the 16th century, small amounts of tea were brought to Russia in the form of expensive gifts from Asian envoys. The exact date of the arrival of Chinese tea to the Russian tsar is known - it is 1567. Two Cossack chieftains Petrov and Yalyshev, who visited China, tried and described this drink, and also brought a box with expensive yellow tea as a gift to the king from the Chinese emperor. In 1638, the Russian ambassador Vasily Starkov brought 64 kg of tea as a gift to the king from the Mongol khan. In 1665, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich was treated with tea. Over time, tea reached Siberia, and researchers in the eastern part of the Russian Empire discovered a widespread use of tea there. By the 17th century, tea in Russia was drunk by boyars and their entourage, it was served at royal receptions and in the houses of wealthy merchants. In the 18th century, noblemen and wealthy merchants were added to these categories, and by the 19th century, tea became widespread.

Initially, tea came to Russia by dry route from China and neighboring countries. Later, with the opening of the Suez Canal, tea began to be supplied by sea. Our ancestors knew only green and yellow tea, they drank it without sugar. Perhaps that is why women did not drink tea for a long time. The bitter taste of the drink was unusual in comparison with traditional Russian drinks (sbiten, honey), which had a sweetish taste.

The tradition of Russian tea drinking is one of the most difficult to describe. Over the past 150 years, there have been so many changes in society and the way of life that it is no longer clear what is considered the main thing in the Russian tradition of drinking tea. For foreigners, a strange Russian samovar, previously used to make sbitnya, is considered a symbol of Russian tea drinking.

The tradition of Russian tea drinking is one of the most difficult to describe. Over the past 150 years, there have been so many changes in society and the way of life that it is no longer clear what is considered the main thing in the Russian tradition of drinking tea. For foreigners, a strange Russian samovar, previously used to make sbitnya, is considered a symbol of Russian tea drinking.

A samovar, a drink from saucers, a glass in a silver cup holder - these are just external features that are available to us from the descriptions of the classics and from the paintings of famous artists of the past. It is necessary to separate the technical side of preparation from the inner, spiritual essence of tea drinking in Russian. Tea in Russia has long been a reason for a long leisurely and good-natured conversation, a way of reconciliation and solving business issues. The main thing in Russian tea drinking (apart from tea) is communication. Lots of tea, treats and pleasant company - these are the ingredients of Russian-style tea. A modern Russian feast often consists of two parts: food and alcohol, and tea with sweets. So, more often it is in the tea (and not in the alcoholic) part that conversations are held, guests indulge in pleasant memories, and interesting ideas arise. The hostess only has time to warm the water, and tea flows like a river and the finished sweets are not a hindrance to its continuation. This tradition also makes practical sense. Unsweetened tea some time after a hearty meal helps digestion, and the guest gets up from the table refreshed and vigorous.

Technically, the brewing process is available in 3 versions. The first is the most "Russian": water is heated in a samovar, tea is brewed in a large teapot, which is placed on the crown (upper part) of the samovar and poured into cups without adding water and sugar. Sweet is taken in this way to eat with a bite. Here, a large volume of the teapot and the heating of all dishes at each stage are important. Tea does not like coolness - it likes heat. In the second method, the samovar is replaced with a teapot, and the teapot is covered with a special tea heating pad so that the heat does not go away - almost the same as in the English tradition. Tea is not diluted with water, and sweet is eaten with a bite. There is a third way, which has its roots in the poor Soviet era. The tea is brewed strong, and this infusion is poured into cups, into which hot water is added. The same procedure is sometimes carried out with a samovar instead of a teapot.

Technically, the brewing process is available in 3 versions. The first is the most "Russian": water is heated in a samovar, tea is brewed in a large teapot, which is placed on the crown (upper part) of the samovar and poured into cups without adding water and sugar. Sweet is taken in this way to eat with a bite. Here, a large volume of the teapot and the heating of all dishes at each stage are important. Tea does not like coolness - it likes heat. In the second method, the samovar is replaced with a teapot, and the teapot is covered with a special tea heating pad so that the heat does not go away - almost the same as in the English tradition. Tea is not diluted with water, and sweet is eaten with a bite. There is a third way, which has its roots in the poor Soviet era. The tea is brewed strong, and this infusion is poured into cups, into which hot water is added. The same procedure is sometimes carried out with a samovar instead of a teapot.

It is customary to drink Russian tea when you have at least half an hour of free time. It is not customary to grab a cup of tea and run on business. It is not customary to remain silent at the table, as is done in the Japanese or Chinese ceremony, and to stand on ceremony and play a "tea show", as is done in England. Silence behind the samovar is regarded as a sign of deep disrespect for the owners of the house. For the "Russian tea ceremony" it is customary to use red (in the European classification - black) Ceylon, Indian or Chinese tea. Greens are not suitable for such a tea party.

The Russian tea tradition has its own established stereotypes, which, in one way or another, affect the perception of tea by the Russians themselves or by the guests of the country.

The Russian tea tradition has its own established stereotypes, which, in one way or another, affect the perception of tea by the Russians themselves or by the guests of the country.

Stereotype one: tea and samovar. The samovar was invented for tea, and only with a samovar is real Russian tea drinking possible.

However, the samovar is far from a Russian invention. Its principle was used even in ancient Rome, where hot stones were placed in a container with water for heating. Later the samovar penetrated Europe and was used to heat water. It is known that Peter the Great, among other wonders, brought from Holland a device resembling a modern samovar. Later, Russian craftsmen made their own version of the device, giving it a sonorous Russian name, and from the end of the 18th century, samovars began to be made in Tula and the Urals. Thus, the samovar “Russified” and was adapted to our needs - first for making sbitn, and then water for brewing tea. I must say that the widespread use of samovars began only in the 19th century.

The second stereotype: Russians drink tea from a saucer or from a glass in a cup holder. Both, undoubtedly, existed, but were optional. They could drink tea from a saucer in a narrow circle of friends or relatives, because in society such behavior was considered vulgar. Also, people from the merchant environment liked to drink from the saucer, who did not accept the European "rules of decency", considering them prim and far-fetched, and proposed their own rules, with which guests felt more comfortable at the table. Later this tradition was "tried on" by the bourgeoisie, copying different versions of tea drinking and mixing them together.

The third stereotype: tea is brewed and then diluted in a cup with boiling water. This custom appeared in the post-revolutionary years, when there was plenty of "lordly" tea, and few knew how to brew it correctly. In an era of scarcity, tea was diluted with water to save money. This "economical" method steals the true taste of tea, turning the aromatic drink into a colored liquid for drinking sandwiches.

The third stereotype: tea is brewed and then diluted in a cup with boiling water. This custom appeared in the post-revolutionary years, when there was plenty of "lordly" tea, and few knew how to brew it correctly. In an era of scarcity, tea was diluted with water to save money. This "economical" method steals the true taste of tea, turning the aromatic drink into a colored liquid for drinking sandwiches.

The fourth stereotype: green tea is bitter and not suitable for Russian tea drinking. It can be bitter in two cases - poor tea or improper brewing. Correctly brewed green tea has a sweetish taste and delicate aroma. And its color is very light, greenish or yellowish, but not intense, but almost transparent. You should not insist on green tea - you need to immediately start pouring it out, as soon as you fill the teapot with hot water. If the tea still tastes bitter, try pouring in less tea leaves or pouring out the finished drink faster.

Another stereotype is that Russian tea drinking had an orderly appearance similar to English. This has never happened before, and this is perhaps the greatest value of Russian-style tea. They drank tea as they pleased, each house had its own traditions. The unwritten laws did not fix and did not make Russian tea drinking dead, as it happened in England.

If we talk about the established tradition of Russian tea drinking, then we can distinguish a certain popular image, an average “brand” of tea in Russian: this is a samovar, a pot-bellied teapot, porcelain cups on saucers, lump sugar and tea treats: pancakes, pies, cheesecakes, bagels and other sweet and not so "snacks". This merchant-bourgeois way of drinking tea began to be considered Russian, since noble tea drinking with its copying of English traditions cannot be considered Russian.

If we talk about the established tradition of Russian tea drinking, then we can distinguish a certain popular image, an average “brand” of tea in Russian: this is a samovar, a pot-bellied teapot, porcelain cups on saucers, lump sugar and tea treats: pancakes, pies, cheesecakes, bagels and other sweet and not so "snacks". This merchant-bourgeois way of drinking tea began to be considered Russian, since noble tea drinking with its copying of English traditions cannot be considered Russian.

It is customary to drink Russian tea several times a day. As a rule, this is 4-6 times, and on the days of fasting and in winter they drank tea more actively. An indispensable attribute of Russian hospitality is tea. Now this tradition has been brought to automatism and involves, in addition to tea, obligatory conversations, treats with sweets (jam, honey, pies, sweets and cookies). For guests in the house there is a special "festive" service, which does not take part in everyday tea parties. The same set is used in the tea section of Russian feasts. In Soviet times, a beautiful tea set was an indicator of the status of the owners. The best were considered "foreign" ones, those that were difficult to find. It was especially important to have a beautiful tea set at home as opposed to public catering glasses with weak, sweet tea.

The tradition of drinking tea from glasses, incomprehensible to foreigners, goes back to the 17th and 18th centuries. At that time, tea in taverns was served in glasses, because European cups and sets were not yet fashionable. Later, glasses were gradually replaced by cups, but in some families it was customary to use such traditional dishes until the revolution. Porcelain cups almost everywhere replaced glasses, but they still remained in taverns: tea, like a rough male drink, was served in the same dishes as cheap alcohol, or alcohol was mixed with tea. In order not to burn your fingers, they made a cup holder. It was rather a marching, railway tableware, which, under any favorable conditions, was replaced by porcelain or faience.

The tradition of drinking tea from glasses, incomprehensible to foreigners, goes back to the 17th and 18th centuries. At that time, tea in taverns was served in glasses, because European cups and sets were not yet fashionable. Later, glasses were gradually replaced by cups, but in some families it was customary to use such traditional dishes until the revolution. Porcelain cups almost everywhere replaced glasses, but they still remained in taverns: tea, like a rough male drink, was served in the same dishes as cheap alcohol, or alcohol was mixed with tea. In order not to burn your fingers, they made a cup holder. It was rather a marching, railway tableware, which, under any favorable conditions, was replaced by porcelain or faience.

The mandatory list of items for classic Russian festive tea drinking included: a samovar or a kettle for heating water, a stand or tray for a samovar, a service that consisted of a teapot, tea pairs (cups and saucers), a milk jug and a sugar bowl, tongs for refined sugar, tongs for chopping refined sugar , tea-pot strainer, vases for sweets. They preferred to take soft spring water for tea. Tea on such water was aromatic and fresh. The brewing method was similar to the English one. In the Russian tradition, however, it is not customary to brew tea as strongly as in England. Russian-style tea was prepared in a teapot and poured into cups without diluting with water. If milk or cream was added, it was warmed up and added to cups before tea. The tradition of making strong tea leaves separately, and then diluting them with water, has taken root in the workers 'and peasants' environment, and for some reason is now considered a folk way. But given that tea with this method turns out much worse than brewed correctly, it is better not to use it.

There is a tradition of completing tea drinking. In the classic Russian version of the 18-19th century, it was a glass or a cup turned upside down, placed on a saucer. A little later, in the European manner, they began to put a spoon in a cup. A teaspoon in an empty cup was a sign that the guest no longer wanted tea. It was impossible to blow on tea to cool it down, and tinkle with a spoon while stirring sugar. Good form dictated that the spoon should not touch the sides of the cup, and after the stirring was over, it should not remain in the cup. Pouring tea into a saucer and drinking from it was also considered contrary to these rules. But, as you know, tea in a merchant way refuted all overseas rules and provided great freedom at the tea table.

There is a tradition of completing tea drinking. In the classic Russian version of the 18-19th century, it was a glass or a cup turned upside down, placed on a saucer. A little later, in the European manner, they began to put a spoon in a cup. A teaspoon in an empty cup was a sign that the guest no longer wanted tea. It was impossible to blow on tea to cool it down, and tinkle with a spoon while stirring sugar. Good form dictated that the spoon should not touch the sides of the cup, and after the stirring was over, it should not remain in the cup. Pouring tea into a saucer and drinking from it was also considered contrary to these rules. But, as you know, tea in a merchant way refuted all overseas rules and provided great freedom at the tea table.

In tsarist Russia, they drank mainly Chinese tea. Until the 19th century, it was exclusively Chinese, at the end of the 19th century, Ceylon and Indian began to appear. Until the 19th century, dry teas from China were highly valued - they did not spoil on the road, did not damp, although they were very expensive. Such tea was appreciated by European gourmets, who did not have access to expensive Chinese tea. They bought it in Russia for a lot of money. In the middle of the 19th century, China sharply cut the supply of tea to Europe, and even banned some varieties from export. For Russia, on the contrary, an exception was made, and our ancestors could enjoy exclusive yellow tea, inaccessible to Europeans.

At the end of the 19th century, teas from India and Ceylon began to be sold in Russia, and the first harvests of tea from Georgia and Krasnodar appeared. Indian tea has always been lower grade and cheaper than Chinese tea. There were exceptions - alpine teas of northern India or the mountainous regions of Ceylon. Such tea went on a mass sale and enjoyed success with an inexperienced public or in taverns. Indian tea could be brewed tightly and sparingly, and its purpose was most often "to drink and warm". Black tea became tea for pies, tavern tea. Later, the same niche was occupied by the Georgian one, which was even lower grade and was sold as part of mixtures (blends). Krasnodar tea has always stood apart from all well-known tea-growing regions. Experiments on breeding the tea bush in rather cold conditions were successful, and the interesting and specific taste of Krasnodar tea found its admirers. However, the labor intensity and high price of "native" tea did not allow and still does not allow it to compete with Chinese and Indian varieties.

At the end of the 19th century, teas from India and Ceylon began to be sold in Russia, and the first harvests of tea from Georgia and Krasnodar appeared. Indian tea has always been lower grade and cheaper than Chinese tea. There were exceptions - alpine teas of northern India or the mountainous regions of Ceylon. Such tea went on a mass sale and enjoyed success with an inexperienced public or in taverns. Indian tea could be brewed tightly and sparingly, and its purpose was most often "to drink and warm". Black tea became tea for pies, tavern tea. Later, the same niche was occupied by the Georgian one, which was even lower grade and was sold as part of mixtures (blends). Krasnodar tea has always stood apart from all well-known tea-growing regions. Experiments on breeding the tea bush in rather cold conditions were successful, and the interesting and specific taste of Krasnodar tea found its admirers. However, the labor intensity and high price of "native" tea did not allow and still does not allow it to compete with Chinese and Indian varieties.

In the 20th century. Chinese tea was drunk until the 70s, when relations with China deteriorated. Since the 1970s, they switched to Ceylon and Indian tea, as well as Georgian and Krasnodar tea, which appeared 100 years ago, but were considered low-grade and were only mixed with inexpensive Chinese and Indian varieties. In the 80s of the 20th century, the quality of imported tea (primarily from Georgia) deteriorated sharply in the USSR. In the 90s, high-quality Chinese tea, along with knowledge of Chinese traditions, seeped into Russia, but the bulk of the tea was of very low quality. Now the stores are dominated by cheap varieties of Ceylon tea, the second most popular is Indian, followed by Chinese, Kenyan, Javanese, Vietnamese, Turkish, Iranian, and Krasnodar tea completes the rating. Georgian tea has completely disappeared from sale due to its poor quality.

In the 20th century. Chinese tea was drunk until the 70s, when relations with China deteriorated. Since the 1970s, they switched to Ceylon and Indian tea, as well as Georgian and Krasnodar tea, which appeared 100 years ago, but were considered low-grade and were only mixed with inexpensive Chinese and Indian varieties. In the 80s of the 20th century, the quality of imported tea (primarily from Georgia) deteriorated sharply in the USSR. In the 90s, high-quality Chinese tea, along with knowledge of Chinese traditions, seeped into Russia, but the bulk of the tea was of very low quality. Now the stores are dominated by cheap varieties of Ceylon tea, the second most popular is Indian, followed by Chinese, Kenyan, Javanese, Vietnamese, Turkish, Iranian, and Krasnodar tea completes the rating. Georgian tea has completely disappeared from sale due to its poor quality.

As for expensive teas, their selection is so great that everyone has the opportunity to choose tea according to their taste.

Story

Legends

Sources of the XVIII-XIX centuries often attributed the "introduction" of tea in Russia to Peter I (along with many other innovations attributed to the tsar, but in reality, often appeared long before his birth, including the import of a samovar from Holland, and drinking coffee , and shaving beards, and "foreign" dress, and the army of the "new model"). In fact, the Russians learned about the existence of tea and began to drink it long before the accession of Peter.

In Russian works devoted to tea and its history, the version set forth in the book "Tea" by V. Pokhlebkin is widely spread, according to which they first learned about tea in Russia in 1567, when the Cossack atamans Petrov and Yalyshev who visited China described the custom of drinking in China , Southeast Siberia and Central Asia, a drink previously unknown in Russia. The version comes from a manuscript published in the 19th century by the famous collector of ancient documents I. Sakharov in the "Tales of the Russian People", however, modern historians generally consider this manuscript to be fake, and the "embassy of Petrov and Yalyshev" itself is fictional.

Documented appearance of tea in Russia

The first reliably documented contacts between Russia and China date back to the beginning of the 17th century: the expeditions in 1608 and 1615 were unsuccessful, and only in 1618 did a detachment of the Cossack Ivan Petelin reach China. It was the description of his journey that formed the basis of the manuscript telling about the embassy of Petrov and Yalyshev, so, apparently, it was during these years that people in Muscovy learned about tea.

Drinking tea in Russia began in the first half of the 17th century, but the exact date of this event also has options. There is a version that already in 1618 Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov received several boxes of tea as a gift from the Chinese ambassadors. It is reliably known that in 1638, four pounds of tea were handed over to the Moscow ambassador Vasily Starkov for Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich by the Mongol Altan Khan Kuchkun in response to the gifts brought by the Russian ambassadors.

The very word “tea” in Russian was first encountered in medical texts of the mid-17th century, for example, in “Materials for the history of medicine in Russia”: “herbs for tea; ramon color (?) - 3 handfuls each ”(issue 2, No. 365, 1665, 291),“ boiled chage (probably chaje or the same, but through the Greek “scale”) to a leaf of Khinskiy (typo: khanskiy) ”( Issue 3, No. 1055, 1665, 788). The name was apparently borrowed directly from the Chinese language, in which (in Cantonese) the words "cha" and "chae" mean "tea-drink" and "tea-leaf", respectively).

Tea imports grew steadily, in fact doubling every 20 years (from 1800 to 1850, it grew from 75,000 poods / year to 360,000 poods / year). In 1840-1850, the import of tea accounted for up to 95% of all Chinese imports to Russia and was estimated at 5-6 million rubles a year (for comparison, in the same period, all exports of Russian grain gave 17 million rubles a year). The tea trade was carried out exclusively on an exchange basis; in exchange for tea, Russian merchants supplied China with fabrics, dressed leather, furs, and metallurgical products.

The development of tea consumption contributed to the rise of those industries that were directly or indirectly associated with the tea trade. So, in Tula, the production of samovars developed widely: if in the second half of the 17th century samovars were produced almost individually, by 1850 there were 28 samovar factories in Tula, the total production of samovars reached 120,000 per year. Russian porcelain also gained fame in the 19th century - originally, tea ware, on the initiative of Catherine II, began to be produced in small batches at the Imperial Porcelain Factory, later numerous private firms were engaged in this. In the second half of the 19th century, the MS Kuznetsov Partnership for the Production of Porcelain and Earthenware Products became the main manufacturer of "mass" tea porcelain, which included many previously independent porcelain and earthenware factories in Russia. At the beginning of the 20th century, the catalogs of porcelain factories contained hundreds of types of tea pairs, sets and individual items of tea table setting, of any shape, size and color, for every taste.

Overland transportation (exclusively by horse-drawn transport) was the reason for the high cost of tea in Russia. From the Chinese border to Moscow, tea transports traveled about 11,000 km, which took up to six months. To the price of tea, in addition to the duty of 80-120% of the purchase price levied by the tsarist government, the costs of transportation, feeding the carriers and security were added, as a result, for the consumer, tea in Russia, in comparable prices, was 10-12 times more expensive than in Germany and England. The situation changed radically only in the second half of the 19th century, when, first in 1862, the import of Cantonese tea delivered by sea to Russia began, and in the 1880s, the Samara-Ufa and Yekaterinburg-Tyumen railways began to function, drastically reducing the time and cost of land delivery of tea. In the same years, the supply of tea to Russia from India and Ceylon began - this tea was delivered by sea to Odessa and from there transported around the country. The price of tea plummeted and became a daily mass drink. In 1886, tea was included in the army's food allowance, and from the mid-1890s it began to appear in labor contracts as one of the parts of wages (paid in "money, grub and tea").

"Tea drinking in Mytishchi, near Moscow", V. G. Perov, 1862

Tea consumption in Russia was constantly growing. By the 19th century, all the estates drank it. In the years 1830-1840, Russian statistics noted that in those areas where tea consumption increased, the consumption of strong alcoholic beverages fell. The structure of Russia's tea imports during the 19th century underwent significant changes. In general, Russia has always consumed more black tea than green tea, but until the early 19th century, high-quality green tea made up a significant share in tea imports. Very rare Chinese teas also came to Russia, for example, yellow Chinese "imperial" tea, which the Chinese sold only to Russians and only for furs. Among black teas, both ordinary varieties and expensive “flower” (tip) teas were imported. A significant share of imports was made up of brick tea; by weight it was imported almost as much as black tea. However, as the absolute volume of tea imports increased in the 19th century, imports of green tea fell rapidly, both in absolute and relative terms. So, if in 1810 12,000 poods of green tea were imported, which was 1/6 of the total volume of imports, then in 1850 - only 500 poods, that is, no more than 1/750 of the total volume (which grew by 4, 8 times) import. After the above-described changes in the supply of tea in the 1860s - 1880s, the difference in the price of high-quality green and black teas reached 6-10 times, which led to an almost complete cessation of green tea imports.

The nobility could afford the highest grades of Chinese tea, expensive and rare, or flavored tea imported from Europe. The merchants preferred not so expensive, but giving a dark infusion teas, which they drank in large quantities, brewing less than in the noble environment. The common people drank the cheapest and lowest grade tea. By the end of the 19th century, counterfeit tea first appeared in Russia, which was consumed mainly by the poorest segments of the population, and also found its way into various low-level catering establishments, such as station buffets.

On the cups of the Sitegin plant in the 60s of the nineteenth century, one can find the inscriptions: "Kyakhten tea and Murom kalach - a rich man is having breakfast."Until the middle of the 19th century, the distribution of tea in Russia was geographically extremely uneven: it was drunk mainly in cities, in the territory of European Russia and Siberia. At the same time, in Ukraine, in the Middle Volga region, on the Don, as well as in Belarus, tea was practically unknown. Until the end of the 18th century, the retail sale of tea was developed only in Moscow (wholesale trade was also carried out at the Irbitskaya and Makarievskaya fairs in Nizhny Novgorod). Even in St. Petersburg, until the middle of the 19th century, there was only one tea shop for the entire city, while in Moscow in 1847 the number of specialized tea shops already exceeded a hundred, and there were more than three hundred tea and other catering establishments where ready-made tea was served. In the first half of the 19th century, up to 60% and most of all tea imported into the Russian Empire was consumed by Moscow, the rest was transported to the cities and estates of Central Russia.

In the second half of the 19th century, the area of \u200b\u200btea distribution began to grow rapidly: tea trade opened in Odessa, Poltava, Kharkov, Rostov, Orenburg, Samara, Uralsk, Astrakhan. And by the beginning of the 20th century, Russia became the leader in absolute tea consumption in the world (excluding China, for which there is no reliable information about its own tea consumption at that time). The total turnover of the Russian tea trade before the First World War reached several hundred million rubles a year, there were tea warehouses and shops in almost all major cities of the country, the import of tea in the early years of the 20th century reached 57 thousand tons per year and continued to grow.

Growing tea in the Russian Empire

At a tea-packing factory near Batumi. The beginning of the XX century. Photo by Prokudin-Gorsky

On the territory of Russia (both the Russian Empire and the USSR, the RSFSR and present-day Russia), the tea bush does not grow in its natural form and there are very few places suitable for its cultivation. Nevertheless, since the 18th century there have been plans to grow "Russian tea", stimulated, on the one hand, by the constantly growing consumption of tea in the country, on the other, by the high cost of imported Chinese tea. In 1792, an article by a certain G.F.Sivers was published, in which it was proposed to buy tea bushes in Japan and create plantations in the Kizlyar region, which at that time was the southernmost point of the Russian Empire. However, things did not go beyond plans and theoretical calculations then.

The first documented case of growing a tea bush in Russia is in 1817, when a tea plant was grown in the Nikitsky Botanical Garden in Crimea. One of the first attempts to grow a tea bush for tea production in Russia was made by Porfiry Evdokimovich Kirilov, doctor of the 11th Russian Spiritual Mission in Beijing (1830-1840). Upon his return to Russia, he brought with him a tea bush and seeds, and at home demonstrated the possibility of growing tea in Russia.

The tsarist government did not pay attention to the production of tea in Russia, therefore, until the October Revolution, tea cultivation was the lot of individual enthusiasts and wealthy landowners. Industrial tea growing on the territory of the Russian Empire began after the Crimean War. A captured British officer, Scotsman Jacob McNamarra married a Georgian noblewoman and settled in Georgia. It was he who created the first small tea plantations on the lands of the Eristavi princes, in the regions of Ozurgeti and Chakva. Already in 1864, "Caucasian tea" was presented at the trade and industrial exhibition. However, this tea was of very low quality and so far could not compete with imported Chinese. After that, attempts were made to grow tea in Georgia, on the lands of the royal family, but the venture actually failed, mainly due to the poor quality of the seed: the seeds purchased from China and Japan turned out to be partly incompatible, partly rotten.

Development of tea production in the USSR

The peak of the development of tea production in the USSR should be considered, apparently, the second half of the 1970s. At this time, the area for tea reached its maximum - 97 thousand hectares, that is, compared with pre-revolutionary times, it increased more than 100 times. There were 80 modern tea industry enterprises in the country, only in Georgia 95 thousand tons of ready-made tea were produced per year. By 1986, the total production of tea in the USSR reached 150 thousand tons, slab black and green - 8 thousand tons, green brick - 9 thousand tons. In the 1950s - 1970s, the USSR turned into a tea-exporting country - Georgian, Azerbaijani and Krasnodar teas were supplied to Poland, East Germany, Hungary, Romania, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, South Yemen, Mongolia. Mainly brick and tiled tea went to Asia. The USSR's need for tea was met by its own production, in different years, by an amount from 2/3 to 3/4.

Simultaneously with the development of its own production, the import of tea from abroad continued. At first, the main supplier was China, then, as Chinese exports decreased (due to internal political processes in China, due to which in some years it did not supply tea to the world market at all), purchases of tea began in India, Sri Lanka, Vietnam , Kenya, Tanzania. Since the quality of Georgian tea, in comparison with imported tea, was low (mainly due to attempts to mechanize the collection of tea leaves), mixing of imported teas with Georgian tea was actively practiced, as a result of which a product of acceptable quality and price was obtained.

By the end of the 1970s, the situation with the USSR's own tea production began to deteriorate rapidly. Georgia, where the bulk of Soviet tea was produced, has almost completely switched to mechanical harvesting of tea leaves, due to which the quality of Georgian tea has fallen dramatically. At the same time, technological discipline also decreased, for example, it was allowed to collect leaves in rainy weather, which is completely unacceptable. Over the next decade, from 1981 to 1991, tea harvest in Georgia fell from 95 to 57 thousand tons per year, and the progressive deterioration in quality led to the fact that the actual production of tea fell by more than fourfold - more than half of the tea leaves received by factories , was rejected as unsuitable for tea production. From what passed the inspection, high quality tea was almost impossible to obtain. Attempts to "improve" (in fact, to speed up and reduce the cost) of the tea leaf processing technology undertaken in Soviet tea factories, in particular, the introduction of post-drying processes at elevated temperatures, "accelerated fermentation" (processing of undried tea leaves in the expectation that it will have time to ferment in the course of other technological operations) additionally worsened the already low quality of raw materials. As a result, low-grade tea with a large number of shoots (popularly referred to as “firewood”) and practically no tea aroma fell on the shelves. Naturally, this led to a reorientation of consumers to imported tea, but it was purchased much less than the general need, as a result, pure Indian and Ceylon tea quickly fell into a deficit, it became almost impossible to buy it in stores - it was imported extremely rarely and in small batches, it was instantly sold out. Sometimes Indian tea was brought into canteens and canteens of enterprises and institutions.

Tea coupon in Leningrad, 1990

Own tea production after 1980 dropped significantly, the quality deteriorated. Since the mid-1980s, a progressive commodity shortage has affected essential goods, including sugar and tea. At the same time, the internal economic processes of the USSR coincided with the death of Indian and Ceylon tea plantations (another period of growth has come to an end) and an increase in world prices for tea. As a result, tea, like a number of other food products, almost disappeared from the free sale and began to be sold with coupons. In some cases only low-grade tea could be bought freely. Subsequently, Turkish tea was bought in large quantities, which was very poorly brewed. It was sold in bulk without coupons. In the same years, green tea appeared on sale in the middle zone and in the north of the country, which was practically not imported to these regions before. It was also sold freely.

Own sorts of tea produced in the USSR are descendants of the Chinese variety "Keemun", although the work carried out by Soviet breeders has significantly changed this variety. Black tea was divided into the following varieties:

- Bouquet - tea of \u200b\u200bthe highest quality with tips (it was called, depending on the origin, "Bouquet of Georgia", "Bouquet of Azerbaijan", "Krasnodar bouquet").

- Extra - high quality tea with tips, somewhat less aromatic than Bouquet.

- Top grade - black leaf tea from the upper leaves, of sufficient quality.

- First grade - black leaf tea, noticeably less quality than the premium grade, with the inclusion of shoots.

- Second grade - low-quality tea made from machine-assembled material, with a large number of shoots and foreign inclusions.

Traditionally in Russia, water for tea was boiled in a samovar that can keep the water hot for a long time, as well as heat the teapot for better tea extraction. During tea drinking, the samovar was placed in the middle of the table, closer to the hostess, or on a small additional table next to the hostess, which was aesthetically pleasing, convenient (no need to leave anywhere to pour more tea for the guest if he wishes) and allowed the owners to demonstrate their level of wealth, one of the symbols of which was a samovar of the greatest possible weight. However, at present samovars (mostly electric) are very rare, usually water is boiled on a stove in a metal kettle, or an electric kettle is used. However, the production of samovars (including wood-burning ones) in Russia is preserved mainly as souvenirs.

Tea glass in a branded "railway" cup holder

For solemn and formal tea parties, porcelain or earthenware tea pairs are served with a small cup (200-250 ml). In home drinking, in some places the tradition of pouring hot tea from a cup into a saucer and drinking from it is preserved. In everyday life, tea is drunk from any suitable size and familiar dishes: cups, glasses, mugs. On the railways, the custom has been preserved to serve tea in a glass cup placed in a cup holder.

A feature of Russian tea drinking, which is still preserved today, is the two-teapot brewing: tea is brewed in a small teapot much stronger than it is drunk - in a teapot with a volume of about half a liter, an amount of dry tea is brewed, sufficient for several people. The concentrated brew is diluted with boiling water directly when pouring into cups, adjusting the strength of the drink to taste. Sometimes, after a single filling, the tea leaves are re-poured with boiling water and infused, but not more than once.

Although the consumption of tea in Russia, unlike the Japanese or the British, is not accompanied by a formalized ceremonial, by the 19th century its own peculiarities of tea etiquette developed, most of which are now forgotten. For example, a guest, having drunk one cup of tea, had to refuse the next until the hostess asked him to continue drinking tea several times.

The variant of drinking tea with sugar is still widespread: they drink unsweetened tea while holding a small piece of hard sugar in their mouths so that the sugar is "washed" by the tea, or they simply bite off a piece of sugar little by little, washing down the sugar crumbs with tea. In the second case, sugar is sometimes pre-dipped with the edge of a piece in tea to reduce its hardness. In the past, drinking "bite" was a tribute to economy, now it is sometimes practiced by tea lovers who believe that adding sugar directly to the drink spoils its taste. Another almost forgotten tradition is drinking tea “with a towel”, according to which a towel “to wipe off sweat” was hung around the neck before tea drinking.

In poor families, a glass or a cup was covered and a piece of sugar was placed on top, which had to be stretched for the whole tea-drinking - this custom was dictated by the high cost of sugar; in the wealthier, they put sugar on the table and put a spoon in a glass or cup. Today, a common spoon is often put in a sugar bowl, with which sugar is placed in cups, while stirring sugar in tea with each spoon.

A tradition that has been preserved is the tradition of pouring a full cup of tea for a guest. Which means the host doesn't want the guest to leave quickly. However, with the spread of the tradition of drinking tea in large (sometimes up to half a liter) cups - before pouring such a full cup, the guest is asked how much to pour.

Peculiarities of drinking tea in different circumstances

Everyday homemade tea

As a rule, in a Russian family they drink tea at least two or three times a day (not counting, of course, those families where they prefer coffee). Tea accompanies every meal, they drink it separately from food. Most often, leaf or granulated black tea is brewed, the brand of which is chosen depending on preferences and financial capabilities. Tea bags are unpopular in Russia, tea connoisseurs usually consider it to be deliberately low-quality and tasteless, and drink it only when necessary, when circumstances do not allow making loose tea. Some lovers specially collect and dry various herbs and berries to add to tea: mint, black currant leaf, St. John's wort, raspberry leaf, rose hips.

Tea is brewed, as a rule, for the whole family, in one teapot, from where it is poured into cups and diluted with boiling water to taste. The teapot can be topped up with boiling water again or twice. Most often, tea is drunk sweetened, or with sweet confectionery (or both at once). Morning tea is usually drunk at the table directly in the kitchen, in the evening tea can be accompanied by watching TV programs.

The most varied utensils for home tea drinking can be chosen - from miniature cups and bowls to huge mugs up to half a liter or more. Often, each family member has their own favorite cup or mug.

Tea in a festive feast

Tea in Russia is an almost indispensable element of a "full-fledged" festive feast, dinner party or dinner. In fact, such a feast is divided into two parts: the first serves food and alcohol, the second - tea and sweets. At the transition to the "tea" part of the dinner, the table is tidied up and set for tea. Although etiquette, generally speaking, does not require uniformity of tea utensils, it is considered preferable to use utensils from the same set for ceremonial and formal occasions. Often the family has a "ceremonial" tea set, which is used only for festive tea parties.

For drinking tea, tea pairs, pie plates, teaspoons, sugar (sand or refined) in a sugar bowl with a separate spoon or tweezers for putting sugar, sweets in vases, pastries cut into portions, sliced \u200b\u200bwhite bread and / or ready-made sandwiches are served dishes. Milk or cream can be served in a milk jug. Lemon is served in thin slices on a saucer, ordinary butter or chocolate butter - on a saucer or in a special oil can. Jam and honey are placed on the table in small vases, usually glass or crystal, with a spoon; guests are served with small rosettes, where they can put themselves jam or honey from a common vase. Balm, rum or cognac can be put on the table to add to tea. A kettle or jug \u200b\u200bof hot water and a teapot are also placed on the table, or placed on an additional table next to the hostess. If a cake is served for tea, then it is placed on the center of the table, the hostess (host) cuts it and spreads it on the guests' plates with a spatula. In the absence of special pie plates (or space for them if the table is small), it is considered permissible to put pieces of cake on tea saucers, while the cups are placed directly on the table.

When pouring tea into cups, the strength of the drink is regulated individually, according to taste, everyone puts sugar and other additives into his cup independently. Sugar is put into a cup with a common spoon (or tweezers), and stir with your own. Unlike English etiquette, which prescribes eating pastries with a knife and a fork, in Russian tea drinking "hard" baked goods cut into portions and sandwiches are taken by hand, cake and "soft" pastries are eaten with a teaspoon.

There is no formalized order of behavior at the tea table, similar to the Japanese tea ceremony, in Russia, on the contrary, this stage of the meal presupposes free conversation on arbitrary topics. The end of the tea party means the end of the feast as a whole.

Separate specially organized tea party

A separate tea party can be organized on purpose, as an option for a short, inexpensive and not requiring complex preparations for spending time together for a pleasant conversation. Moreover, it proceeds in approximately the same way as in the previous case; the measure of observance of etiquette formalities, the range of sweets, pastries and other snacks for tea may vary greatly, depending on the capabilities of the organizers (participants), the level of their acquaintance with each other and time constraints. Sometimes such tea-drinking is organized regularly or from time to time during a break at the workplace (office); in these circumstances, tea bags are usually drunk with a poor selection of pastries brought from home or bought at a nearby store.

Receiving unexpected guests

In Russia, it is customary to serve tea to a guest who is on a visit, including an unplanned, official, or related to any side circumstances (who came to take or give something, inform, invite, and so on). Offering a cup of tea in such circumstances is considered a sign of hospitality, especially in the cold season, when it is assumed that a guest who came from the street could chill. This custom has long since passed from home culture to office culture, and now in the office it is considered almost obligatory to offer a visitor tea or coffee, if circumstances and time permit it, especially when he has to wait for some time.

As a rule, no serving and culinary delights are expected, any available tea is served (in the office, as a rule - in bags), if there is an opportunity to choose, they ask the guest what he prefers; tea is served with sugar and, possibly, something from ordinary confectionery. Tea is served where it is more convenient in specific circumstances, the host can accompany the guest for a tea party, but he may not do this, but simply be present; the second emphasizes that the host considers it necessary to fulfill the duty of hospitality, but prefers to move quickly to the immediate purpose of the visit.

Tea in Russian culture

In language

The word "tea" in Russian is consonant, and in some grammatical forms it is similar to the now obsolete verb "to see" (to see, to know). Due to this consonance, earlier - in the spoken language, and now - mainly in literature, you can find various variants of puns on the topic "tea - tea", like: "For tea, you need to drink tea" (the first "tea" is the first person singular from " to expect ”, the second is genitive singular from“ tea ”).

There is also a number of catchphrases on the tea theme in Russian. For instance:

- "Drive teas" (with an emphasis on the final "i") - about unhurried tea drinking in a small company, not limited by strict time frames, for the sake of a pleasant conversation or just as a means to while away the time when there is nothing else to do. It can be used in a negative connotation, as a synonym for "idle, useless to spend time", for example: "Why don't people work? Have you come here to drive teas? "

- "[By] indulge in seagull" - a more expressive synonym for the neutral expression "have tea". It can be applied to tea drinking "on occasion" when the moment is right.

- "Tea and sugar!" (outdated) - a polite phrase that was uttered by a guest who came at an inopportune, not previously agreed time and found the owner drinking tea. An analogue of the much older "Bread and Salt!", Used when the guest found the hosts dining. In response to "Tea and sugar!" the hosts could invite the guest to join the tea party.

- "They didn't even offer tea" - characteristic of an extremely cold, unfriendly reception.

- "[Will you] not even have tea?" - a phrase addressed to a visitor who is going to leave immediately; expresses a light, polite reproach for the transience of the visit and regret of the owner about this.

- To Tula with his samovar - stock up on the travel items, which are in abundance wherever you go (the city of Tula, one of the largest centers of samovar production in pre-revolutionary Russia, is played up).

Tea drinking traditions have spawned a set of "tea" proverbs and sayings, such as:

- Tea is not vodka - you can't drink much.

- Drink tea - do not chop wood.

- Don't be lazy, but tell where is straw and where is tea!

- Drink some tea - you will forget longing.

- We do not miss tea - we drink seven cups!

- Come to tea - I treat you to pies.

- We have Chinese tea, sugar is the master's.

- Nobody choked on tea in Russia!

In literature

Antiochus Cantemir, in his comments on his Second satire "To the envy and pride of malevolent nobles" (written in Russia, went to the lists, published in 1762) notes:

Everyone knows that the best tea (a fragrant and tasty leaf of the so-called tree) comes from China and that, by putting a pinch of that leaf in hot water, that water becomes, by attaching a piece of sugar, a pleasant drink.

Tea in the life of the landowners of the 19th century is repeatedly mentioned in the poem "Eugene Onegin" by Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin. So, for example, tea is treated to a welcome guest, a possible candidate for groom:

… They call a neighbor to the samovar, And Dunya is pouring tea; They whisper to her: "Dunya, take note!" Then they bring a guitar: And she will squeak (my God!): “Come to me golden!” ..

Tea is an indispensable attribute of evening gatherings with neighbors, reception, ball:

... In the evening, sometimes a kind family came together Neighbors, Unceremonious friends, And to press, and to speak out loud, And laugh about something. Time passes; Meanwhile, Olga will be ordered to cook tea, There is supper there, and it's time to sleep there, And the guests are coming from the yard. ... It was getting dark; on the table, shining, The evening samovar hissed, Heating the Chinese teapot; Light steam curled beneath him. Poured by Olga's hand, Through the cups in a dark stream Already fragrant tea ran, And the boy served cream.

Tea is served in the morning to the hostess in the room:

... But, quietly unlocking the door, Already her gray-haired Filipyevna Brings tea on a tray. "It's time, my child, get up"

The term "globalization" had not yet been invented, and goods were already wandering around the world, bringing borrowed tastes, habits, and manners into every culture. In the same way, foreign tea penetrated into Russian life imperceptibly and unobtrusively. The exact date of its appearance in Russia remains open to question. One gets the impression that samovars were boiling in huts from time immemorial, and tea drinking has always been a primordial Russian tradition.

At the time of Ivan the Terrible, people knew about tea only by hearsay. The first to tell about the unusual drink are Russian ambassadors, Cossack chieftains Yalyshev and Petrov, who returned in 1567 from a Russian trip to the Chinese Empire. However, historians found evidence that a hundred years earlier, in the middle of the 15th century, during the reign of Ivan III, Eastern merchants had already brought tea to Russia.

In 1618, Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov received a royal gift from the Mongolian Altyn Khan - four pounds of tea leaves. The drink did not impress the courtyard, and ordinary Muscovites did not feel anything for tea except curiosity.

The second tsar of the Romanov dynasty, Alexei Mikhailovich, had problems with digestion, and the healers would drink tea for him. The result pleased everyone, the "vitality" of the tea drink was highly appreciated. In medicinal recipes of that time, tea figured as a medicinal ingredient, and this was its main use.

Soon trade agreements were signed with China, and tea became an object of exchange, most often for valuable furs. The quantity of goods was then measured in camels, and the product was transported in cibics.

Tsibik is a bag or box lined with raw leather and filled with dry tea weighing about 40 kg.

The superficial acquaintance of Russians with the fragrant drink grew into true love thanks to Catherine II, who herself had a weakness for overseas potions. The invigorating properties were noticed, its taste was appreciated, and communication with tea began to bring pleasure.

During the reign of Catherine II, six thousand "loaded camels" of tea leaves were used per year. The Empress personally supervised tea caravans and tableware production at the Imperial Porcelain Factory. Under her, Moscow quickly became the tea capital of Russia.

Over the vast Russian vast expanses of horse-drawn carts, the convoy traveled from China through the whole of Siberia and further to Moscow for more than six months. Therefore, tea was a very long-awaited, expensive and inaccessible product for a commoner.

During the reign of the Romanovs in the 17th century, royal receptions were held with tea drinking. It was drunk by boyars and rich merchants, who, moreover, seized on the "tea business" and began to make a fortune on it. Only in the next century did tea spread to the middle-class nobility and merchants.

In Russia, there was a tendency to displace traditional Russian drinks (sbiten, honey), which had a sweetish taste. This is probably why women did not like him because of the bitterness, especially since they initially drank it without sugar. Strong tea was considered a man's drink.

In the second half of the 19th century, Indian and Ceylon varieties were also imported through the Odessa port, and railways were connected to the transportation. In a short time, tea turned into an affordable product, and towards the end of the 19th century, it was drunk by all classes of tsarist Russia. At the same time, low-grade cheap varieties appeared on the market.

How different classes drank tea

Tea gradually descended through the hierarchical levels of society to the very bottom. Each stratum of the population tried to imitate their superiors, but due to limited opportunities, they brought something of their own and adjusted the tea ritual for themselves.

Refined aristocrats copied the English in many ways - impeccable table setting, beautiful dishes, milkman. Here they used expensive Chinese tea of \u200b\u200brare sorts, which was brought dry and brewed at the table.

The nobles initially, before the advent of porcelain tea ware, drank it from carved glasses in cup holders. An integral part of tea drinking was communication, in fact, for this purpose, the company gathered at the tea table.

Merchants and wealthy landowners put their prosperity on display and measured their wallets. The tea ceremony was a great opportunity to stand out, so it was furnished with all the pomp and attributes of abundance: a samovar, various jams, honey, a variety of sweet and salty pastries.

The tea-drinking lasted long and thoroughly, the cups were filled many times. They drank tea from a saucer. Considering the amount drunk, the tea leaves were made very strong so that they would last for a long time, and they were diluted in cups with boiling water. The varieties used are such that they give a rich dark color.

The bourgeoisie - officials, shopkeepers, innkeepers, and city dwellers - imitated the wealthy estates, and gathered for tea like aristocrats. Lacking financial resources, they still tried to set an abundant table in a merchant's manner.

Tea was expensive, so they took the cheapest variety and diluted it to a translucent state. The snacks were simple. The gatherings were accompanied not only by conversations, but also by songs, often performed with a guitar.

It is believed that the Russian urban romance with a guitar arose and took shape in a musical genre during the time of bourgeois tea parties. With a simple and small tool, it was comfortable to sit at the table.

The culture of tea drinking developed in tsarist Russia in public catering. In taverns, tea was served in two teapots, which were placed one on top of the other and were a prototype of a samovar: boiling water in the lower, tea leaves in the upper. The visitor himself prepared a drink of the desired strength. Tea was drunk from glasses, which were also used for alcohol.

The teahouse usually consisted of two rooms. One had large tables on which a samovar and a teapot were displayed. Tea was diluted to taste and drank with snacks. In another room, business issues were resolved, meetings were held and documents were drawn up.

Characteristic features of Russian tea drinking

For some reason, Russians are more fond of black tea. "Tea" has become synonymous with heart-to-heart conversation, a sign of hospitality and a mandatory final stage of the feast. English stiffness and commitment, Japanese and Chinese subtleties of the tea ceremony in Russia did not take root. Here the formalized order of tea drinking has been completely shaken off.

The Russian soul requires scope, openness and sincerity. Tea traditions in Russia are inseparable from detailed conversations on any pressing topics. Tea is drunk any number of times, in winter more often than in the warm season. Sweet must be attached to it - jam, pastries, honey, sweets.

For guests in many houses there are festive sets: dining and tea. In Soviet times, such special dishes were an indicator of well-being and status in society. All housewives, in order to somehow join the elite, dreamed of the "Madonna" mother-of-pearl service.

Festive table

Two stages of the Russian feast always remain unchanged: main courses with alcoholic drinks and tea with desserts. During the change of the table, the guests, tired of the plentiful meal, go out to smoke and powder their nose, and tune in to a leisurely tea party and frank conversations. Strong tea aids digestion and invigorates.

Such continuation of the feast saves from the consequences of overeating and excessive intoxication. Table setting and tea brewing method depend on the hostess. Candy, honey, sugar, jam, lemon slices, pastries or cake, milk / cream in a milk jug are displayed.

Special "sweet table"

So it is customary to call an economical kind of feast, cut down to tea drinking. It is used for various reasons: organizers want to quickly mark an event without etiquette formalities, there is little time for communication, circumstances do not allow setting a full-fledged table, and so on. Often in such cases, they take tea bags and a minimum set of sweets in disposable dishes or put together a table.

At home

Russians drink tea several times a day, at home and at work: as a "third" after the main meal or separately, with or without dessert. Usually, both at home and in the office, everyone has their own favorite cup. They often drink it in front of the TV.

Lovers add aromatic herbs or spices to tea leaves. If tea is prepared for the whole family, it is insisted in a teapot and diluted with boiling water in cups. Boiling water is added to the teapot 1-2 times as it is empty.

Unexpected guests

Treating yourself to tea is a common sign of hospitality, even if a person did not come to visit, but for some purpose. Especially in cold weather it is sacred to offer a cup of tea to a chilled visitor. There are no fixed rules here.

If desired, the host can keep the guest company or offer something from sweets, but he may not. This tradition is also followed in offices, depending on how much time the visitor spends there.

Russian-style tea drinking is very democratic - each house has its own traditions and recipes. Tea is brewed in different ways. They are all extremely simple. The main feature was and remains "two-teapot" brewing and good heating.

- The happy owners of the samovar put a large teapot in a special nest on top. As the water warmed up in the samovar, a vessel with tea was warmed up. The drink was poured into glasses, without diluting, and they drank a bite with sweets.

- If there was no samovar, then a teapot and a teapot would make up a "tea pair". The tea leaf was poured with boiling water in a teapot and insulated for infusion. A beautiful special heating pad - "woman" was often sewn for him. This tea was served undiluted, with a bit of sweets.

- The third method, perhaps the simplest, most economical and popular in Soviet times: a very strong infusion was made in a teapot, poured into cups little by little, and topped up with hot water.

Tea must be given its due - it has gained such popularity that it completely replaced traditional Russian drinks from everyday life. At the same time, I did not even have to invent dishes. Russian sbiten was always prepared in a samovar, which in composition resembles non-alcoholic mulled wine.

Sbiten: A very thick dark red broth is prepared from molasses mixed with spices (St. John's wort, capsicum, bay leaves, sage, ginger, nutmeg) and poured into jars. The viscous liquid is diluted as needed with water and sugar is added.

Fruit drink and mead were also popular drinks. With the advent of tea, the samovar was "retrained" for "tea making".

Popular types

Tea gourmets appeared in Russia immediately. The country received very rare elite varieties of Chinese tea, including the yellow imperial and expensive representatives of the black "flower".

There were several hundred Chinese shops in Moscow, where the choice of green and black was very rich. Muscovites fell in love with the green teas "Imperial Lyansin" and "Pearl Selected", yellow "Yunfacho with flowers" and white varieties "Silver needles". The northern capital preferred the delicate taste of flower varieties.

In big cities, the choice of tea was easier. Residents of rural areas did not understand elite drinks and were not puzzled by varieties and quality. Firstly, not the best and cheapest varieties went on sale to them, and secondly, due to high prices, the peasants preferred to prepare fees instead of them:

- "Koporskiy" made from dried herb Ivan-tea;

- "Wooden" from leaves and bark of trees (, from oak, ash);

- herbal preparations;

- from leaves and fruits of fruit trees and berry bushes.

Unscrupulous businessmen, willing to use any trick to capitalize on the popularity of the product and benefit from such a rich assortment of alternative drinks. This is how counterfeit teas appeared.

They had to look like real ones, so homemade preparations were processed with dyes, often poisonous, mixed with unnatural additives and passed off as a natural product. The worst kind of such activity was the manipulation of the sleeping tea leaves that were collected in tea establishments. The government has developed a suppression scheme and a punishment system for counterfeit traffickers.

Thanks to folk ingenuity, many recipes for alternative drinks have been tried. Some of them were so popular that they became popular. This is how the concept of "herbal tea" came into use in Russia.

Stereotypes

The traditions of Russian tea drinking have developed their own clichés that influence its assessment. Non-existent forms and facts are attributed to him, but:

- The samovar is not a Russian invention, but it has been used for a very long time, first for sbitn, then for tea.

- A saucer - drinking from it is considered vulgar. But whoever has tried it knows - it really tastes better. So it was accepted in the merchant, and later bourgeois environment.

- A glass with a glass holder is a tea exhibit, a tribute to the time, the echoes of which have remained on Russian trains. Still, good tea in a glass is great. Especially when you look at the light.

- Baba for a kettle - a toy with wide skirts can be replaced by a funny chicken or a multi-colored rooster with wings spread over the kettle. In extreme cases, a master's hat will come off. If only the tea does not freeze.

- Tea leaves - why not, so as not to mess around with endless brews in the midst of a conversation.

Tea is a versatile drink that simultaneously nourishes, invigorates and soothes. It's nice to be with him in company and alone. And even reading about him is good at tea.

photo: depositphotos.com/island, Forewer

Tea is one of the favorite drinks of more than half of the world. Tea quenches thirst, invigorates, and sometimes even heals. However, for Russia, tea drinking has become a real tradition. Many proverbs and sayings, songs and poems have been put together about tea drinking. Even guests in Russia are called “for tea”. So what is interesting about the culture of domestic tea drinking?

The history of tea drinking in Russia

It is generally accepted that tea appeared in Russia in the 17th century. It is known for certain that he arrived from China. Tea invigorated and helped fight drowsiness, so initially we used it as a medicine. But later, the drink was so fond of the Russians that in the same century, an agreement was signed between Russia and China for the supply of tea.

Tea became a particularly desirable drink during the reign of Catherine II. The drink really loved to know. Tea drinking has become a whole ceremony. At tea and at home conversation went well, and state affairs were better resolved. Related industries helped to spread tea throughout the country. Samovars, porcelain dishes, which were considered exclusively "tea", appeared.

Tea traditions and customs

Since tea was initially available only to the high class, many tea traditions in Russia came from them.

- Solemnity of the moment. By the time of tea drinking, according to custom in Russia, they carefully prepared. They laid a light-colored tablecloth, put on a shiny samovar, and baked sweet and savory pastries.

- The rich decoration of the table is traditional for tea drinking in Russia. Tea was drunk with milk or honey. They also washed them down with pastries and sweets.

- Tea drinking usually lasted a long time. Now the time for this process has been greatly reduced. Previously, you could drink 5 to 20 cups of tea.

Tea for everyone

In Russia, there was far from one kind of tea. Because later tea began to be supplied not only from China, but also from India, as well as by sea. There are varieties with additives. In St. Petersburg they loved to drink Chinese tea with jasmine. However, due to the high cost of the drink, counterfeits often occurred. Under the guise of Chinese tea, ordinary herbal preparations could be sold. Such "teas" were made from oregano, willow tea, bark and leaves of trees, as well as chopped fruits and berries.

- Drinking tea from a saucer was considered vulgar among the aristocracy.

- In order for the tea to brew as soon as possible, a special "woman" was used for the kettle - a heating pad, which helped to keep the drink warm for a long time.

- Romance (musical genre) appeared precisely during tea parties. Since many topics were discussed at the table, it was not difficult to impose "life" verses on music.